In a previous post on horror movies, I examined why I gravitated toward John Carpenter titles in my youth. Today, I’d like to explore other films I watched a while back, trying to discover patterns in what struck me.

In addition to the Carpenter films, I also watched:

The Slumber Party Massacre (1982)

The Mummy’s Hand (1940)

Son of Frankenstein (1939)

The Invisible Man Returns (1940)

Deathdream (aka Dead of Night, 1974)

Basket Case (1982) rewatch

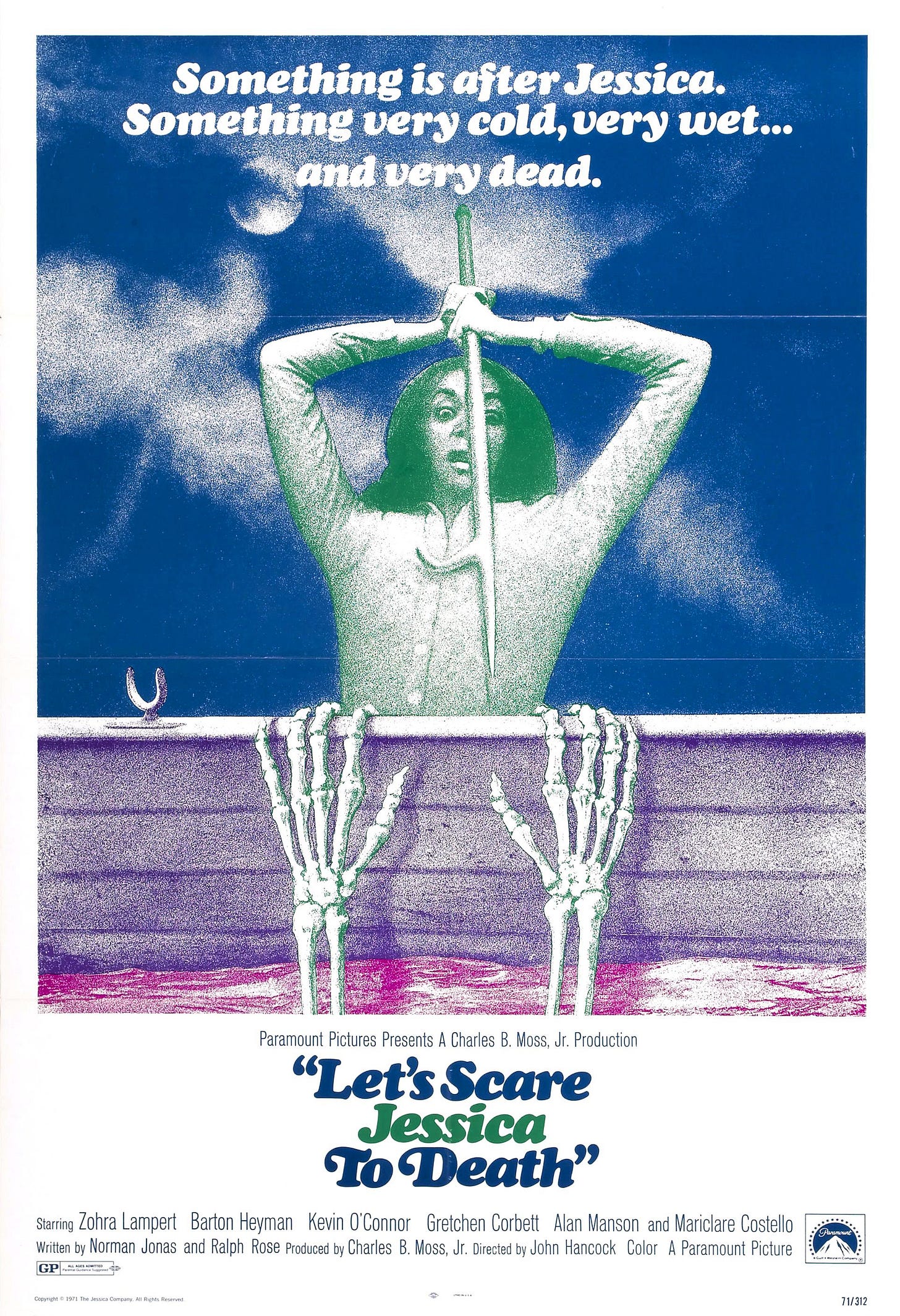

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971) rewatch

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (1951)

Tucker and Dale vs. Evil (2010)

Death Line (aka Raw Meat, 1972)

Black Christmas (aka Silent Night, Evil Night, 1974)

Frightmare (1974)

Alice Sweet Alice (1976)

The Tomb of Legeia (1964)

Sweetheart (2019)

Mother (2009)

November (2017)

The Woman in Black (1989)

Christine (1983)

Midsommar (2019)

Carnival of Souls (1962)

As much as I enjoy the “essentials” of the Universal Monsters movies (original versions of Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Invisible Man, and The Creature from the Black Lagoon), their sequels are often disappointing. While I love The Bride of Frankenstein and Dracula’s Daughter, my initial viewings of other series films such as The Mummy’s Hand, Son of Frankenstein, and The Invisible Man Returns lacked strong storytelling and engagement compared to their originals. That’s to be expected; they’re sequels, and Universal was trying to maximize those properties while tickets were selling.

Son of Frankenstein was the best of this bunch, largely due to the presence of Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. I had to keep reminding myself of what I normally tell my in-person and virtual movie discussion groups: place yourself in the minds of audiences at the time of a film’s release. My expectations for these films should differ from those for current pictures. I appreciate that the filmmakers had to find ways to make these properties fresh and interesting. While they each contain enjoyable moments, I realized I didn’t want to see any more of them. Even today, it seems rare for any film in a series to come close to the original. It’s the law of diminishing returns.

I also watched two Vincent Price films from 1964, The Masque of the Red Death (above) and The Tomb of Ligeia, both loose adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories, both American International pictures, and both directed by Roger Corman. Anything would’ve been a let-down after watching the strangest of the Corman/Price films, The Masque of the Red Death, but The Tomb of Ligeia was also fun. Corman created wonderfully atmospheric stories, and, of course, Price is the icing on the cake.

Again, remember that in the early to mid-1960s, many horror films were still in black-and-white. The Corman/Poe films are not only in color, but glorious color. I don’t know if kids still read Poe, but my friends and I did, and these movies made us want to devour even more of his tales. The blood and violence, combined with jump-scares and creepily atmospheric sets, made these films a big draw then and now. Yet, like the Universal Monsters films, I realized I couldn’t watch many of them in a row. These movies were fun, but the experience faded quickly. These pictures never caused me to examine myself or my fears very much.

I’m no horror historian, but it seems the 1970s allowed filmmakers to open closed doors, or at least to open them wider. For a low-budget picture with no stars, Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971) offers the psychological element of Jessica (Zohra Lampert) being released from a mental ward and starting a new life with her husband (Barton Heyman) and friend (Kevin O’Connor) is compelling and engaging. Its lack of stars provides a sense of realism, as does the on-location shooting in Middlesex County, Connecticut, and the (most likely) non-actor townspeople. Let’s Scare Jessica to Death requires the audience to wonder (1) if Jessica is crazy, and (2) what we would do in her situation. Remember, she’s just been released from an institution, but can she trust anyone? Maybe she shouldn’t have been let go. The leisurely pacing and minimum use of effects make the film compelling and rewatchable.

Let’s linger in the ‘70s a bit longer, focusing on two films directed by Bob Clark, Deathdream and Black Christmas, both from 1974. (Yes, this is the same Bob Clark who gave us Porky’s, A Christmas Story, and one of my favorite Sherlock Holmes films, Murder by Decree.)

In the opening of Deathdream, we see U.S. soldier Andy Brooks (Richard Backus) being shot by the enemy and falling to the ground, dying as his mother’s words, “Andy, you’ll come back. You’ve got to. You promised,” resonate in his thoughts. Skip to Andy’s parents, Charles and Christine Brooks (John Marley and Lynn Carlin), who receive a telegram informing them that Andy was killed in combat. Yet soon afterward, Andy comes walking through the front door. Although the family is delighted that the telegram was erroneous, something is odd about Andy.

Deathdream is not only a commentary on war, death, and the plight of returning Vietnam veterans, but it’s also a very effective horror film that takes its time, delivering palpable dread and fear. You see this theme of having your dead loved one returned to you repeated in later films such as Pet Sematary (1989) and practically every zombie movie ever made. But it’s not only veterans returning home as damaged people that creates terror. It happens with dementia and Alzheimer’s patients as well. Having had a loved one suffer through dementia, I can tell you, it’s terrifying, devastating, and exhausting, showing you that the people you love have turned into someone else, someone you no longer understand. Deathdream captures that feeling of helplessness and horror unforgettably.

Bob Clark’s Black Christmas is disturbing in a different way from Deathdream. The premise is simple: the residents of a sorority house are being harassed on the telephone, then killed off one by one during Christmas break. Clark keeps us guessing right up until the finale. Although all the actresses playing the “college girls” are much older than their characters, they are otherwise believable and engaging. Clark’s ability to sprinkle in lighter moments between scenes of mayhem works well. Black Christmas takes advantage of many locations and features multiple shots inside the sorority house, giving us the feeling that a killer could easily navigate the rooms and hidden areas without being seen. The ending leaves us with the sense that some horrors - on the screen and in life – are never neatly wrapped up. A good cast (Olivia Hussey, Margot Kidder, Keir Dullea, John Saxon, Andrea Martin) makes this a creepily effective horror movie I plan to revisit often.

Death Line (aka Raw Meat, which might be a more accurate title) has problems in finding a balance in tone (with too much attempted comedy for me) and suffers from uneven performances, but is an immensely unnerving movie. Death Line also includes a silent seven-minute scene that few filmmakers today would be bold enough to show.

The creators of Alice Sweet Alice (1976) have some serious issues with Catholicism (its original title was Communion), the emotional neglect of children, and the breakdown of the family. When nine-year-old Karen (Brooke Shields, in her first movie) is murdered during her First Communion, the prime suspect is her jealous twelve-year-old sister Alice (Paula Sheppard), but that’s just one of the plot points in this film. The 108-minute movie may be too long with too many story threads, yet Alice Sweet Alice is often chilling, balancing horror and suspense. As you might imagine, the Catholic church was outraged by this film, which led to several edited versions over the years. (Most DVDs and Blu-rays now feature the full version.) Regardless of your faith (or lack thereof), Alice Sweet Alice examines some uncomfortable territory.

My favorite and possibly the most disturbing film I saw from the ‘70s was Frightmare (1974), which was my first experience with director Pete Walker. The picture has been called the UK’s answer to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which may be a fair comparison. Jackie (Deborah Fairfax) believes her parents, Edmund (Rupert Davies) and Dorothy Yates (Sheila Keith), may have been released from an insane asylum and declared safe a bit too early. That’s all I’ll tell you about the plot. The film is unnerving and, like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, delivers an ending you’re probably not expecting—one that may keep you up at night. Frightmare calls into question several beliefs that audiences had firmly embraced in the early-to-mid-1970s, becoming something of a game-changer for the horror genre.

These ‘70s movies grip you, burrowing under your skin and forcing you to confront not only frights and horrors on a surface level but also stirring up deeper anxieties and fears. Monsters and jump-scares are one thing, but primal nightmares are another—experiences that don’t necessarily fade away once the end credits roll.

Do I want to revisit such films? Maybe. There aren’t any ‘70s movies from this list that I would not revisit. Surface scares are fine, but you’ll find greater significance in each, examining concepts of depth and lingering importance.

Which brings me to one conclusion: Horror movies enable us to confront the real horrors of life. We try to understand truly evil people who commit terrible, violent acts against others. Yet we also confront sickness, mental illness, incurable diseases, losing our faculties, fears of judgment, being abandoned, unloved, scorned, and ridiculed. These are frightening, and horror films can help (at least partially) deal with anxieties and fears. At least it’s a first step.

Next, more current horror movies. Thanks for reading.

Son of Frankenstein has always been a favorite of mine. I've long been a fan of Basil Rathbone (really a better fencer than Errol Flynn) and I think it's the most expressionistic of all the Universal classics.

Dario Argento's movies were the ones that made me most uncomfortable.