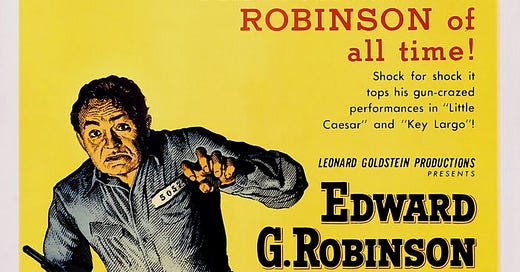

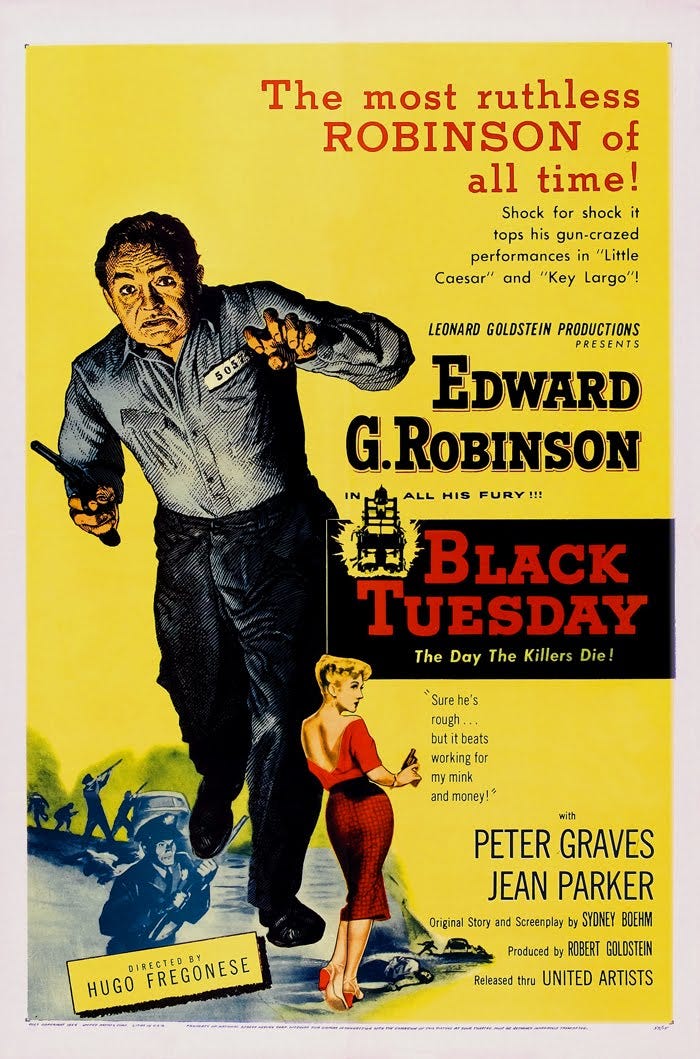

Black Tuesday (1954) is one of the angriest, grittiest, most unflinching movies in all of film noir, due in large part to Edward G. Robinson’s stellar performance as Vincent Canelli, a ruthless and utterly terrifying gangster. The film, along with two other crime pictures starring Robinson, is now available from Kino Lorber as part of their ongoing presentation Film Noir: The Dark Side of Cinema. This Blu-ray collection, Volume XVII in the series, also includes Vice Squad (1953) and Nightmare (1956).

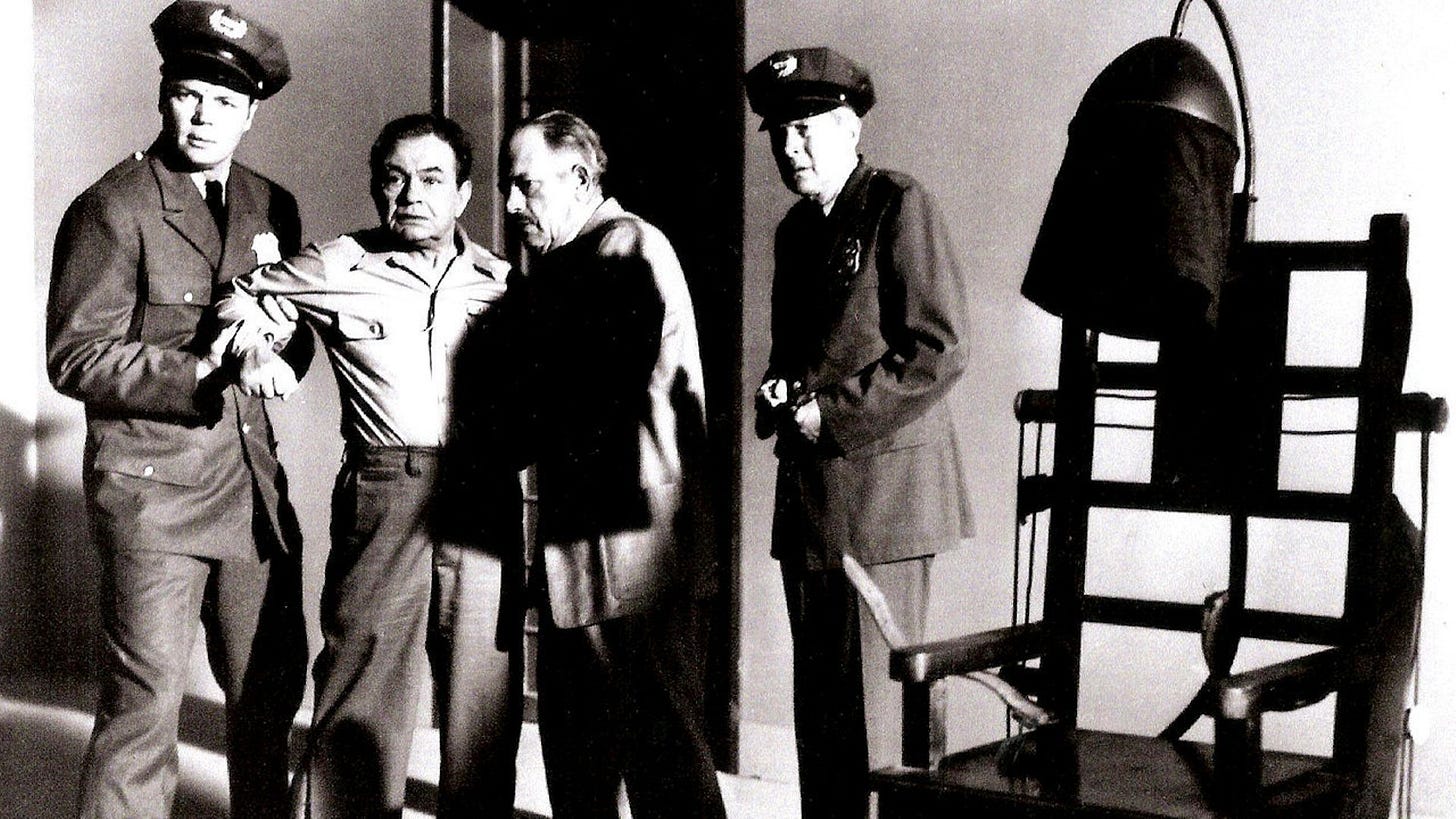

As the film opens, Canelli is trapped behind bars, awaiting Black Tuesday, the day death-row inmates are scheduled for the electric chair. Canelli paces like a caged animal, daring anyone to get close enough to his cell (which one guard does, to his regret). Not only does Canelli show no signs of fear or remorse, he delights to intimidate everyone within the sound of his voice including fellow inmates, the warden, a priest, and probably even God Himself. Yet Canelli won’t walk to the chair alone; also scheduled to join him is Peter Manning (Peter Graves), a man who killed a cop and made off with $200,000. Manning is nowhere near as hardened as Canelli, but Manning has some prime bargaining power: he knows where the money is stashed, and the warden is willing to grant Manning ten more days of life if he’ll cough up the dough. Yet Manning refuses to budge for anything less than a commutation of his death sentence.

Meanwhile, Canelli’s girl Hatti (Jean Parker) and his man on the outside, Joey Stewart (Warren Stevens), kidnap a prison guard’s daughter to secure the guard’s help in Canelli’s escape. Of course the set-up is absolutely implausible, but at this point, who cares? Director Hugo Fregonese sustains the tension at a fever-pitch, and you simply can’t take your eyes off Robinson. Even when Canelli takes far too many hostages for the thing to be believable – a priest, the death chamber M.D., a reporter, and the daughter of the prison guard – we’re riveted with suspense rather than bursting with laughter.

I’m not sure anyone knew how good Black Tuesday was when it was released on New Year’s Eve, 1954. I’m not even sure how many people saw it, but if they did, how did they take it? The pre-execution scene conveys the feel of a sporting event complete with a gallery of chairs set up with men jockeying for the best seats. The warden even goes thorough the rules like we’re about to witness a heavyweight fight rather than the end of a man’s life. You might well call it “Tuesday Night Executions.” Although I’m sure the film was not primarily intended as a statement on the death penalty, that issue is certainly there.

I’m also not sure how large (or small) the budget was, but Black Tuesday was an independent picture produced by the short-lived Leonard Goldstein Productions, distributed by United Artists. The film may have had a low budget, but the people making it were top level. Stanley Cortez, an A-list cinematographer (The Magnificent Ambersons, The Night of the Hunter, The Three Faces of Eve, and an uncredited Chinatown) shot the movie on Kodak’s high-speed, black-and-white Tri-X stock film, which works well for dimly-lit sets, fast action, and depth of field. Perhaps it’s due to the condition of the print Kino had to work with, but the definition of the images isn’t as sharp as it should be. This is certainly not a deal-breaker, but it’s a bit annoying.

Screenwriter Sydney Boehm had just come off writing the screenplay for The Big Heat one year earlier. Edward G. Robinson, of course, was a major star, but was fighting his way back from having his life practically torn apart. (For more on Robinson’s downfall and return to greatness, see this excellent post at Where Danger Lives, yet know that the review of the film includes spoilers.) Black Tuesday also features a small part for Russell Johnson and an uncredited appearance by William Schallert. Yet for all this it’s clearly a B picture and a fine one.

One of the most amazing relationships in the film is that between Canelli and a priest, Father Slocum (Milburn Stone, who would one year later begin his most famous role as Doc in the TV series Gunsmoke). Early in the story, Canelli rebuffs the priests’s offer to administer last rites or anything having to do with the faith. Throughout, Father Slocum shows no fear in Canelli’s presence.

Canelli: “You’re as tough to figure out as some of these gadgets.” (Canelli is playing with electronic children’s toys.)

Slocum: “I’m protected. The only kind of protection worthwhile.”

Canelli: “You’re not scared to die?”

Slocum: “No, Vincent, I’m not.”

Nodding at the gun Canelli’s holding, the priest says, “That’s your kind of courage.”

There’s another scene late in the film between Canelli and the priest. I’m not going to tell you what brings it about or how it ends, but this moment is quietly spectacular. In it we learn that perhaps it’s possible to get underneath the rough exterior of a man like Canelli, that maybe the gangster realizes that Slocum has something Canelli doesn’t: grace and forgiveness, two gifts that could possibly be his. This is a short scene, yet one that’s filled with depth and a theological awareness that could’ve seemed trite and overplayed, yet Canelli seems as if he’s genuinely struggling with this thing called grace that seems too good to be true. But what if it is true? In the midst of a film that’s clearly a survival-of-the-fittest showdown, this moment of grace is a real shock to the system.

The last fifteen minutes blaze with tension, anxiety, action, and the hard-edged consequences of a life of crime. One of the most amazing moments occurs when the police inspector – clearly exhausted by trying to end the standoff with a minimum of lost lives – admits, “I want you to know how it is with me, Father. God forgive me, but I can’t help any of you.”

Black Tuesday is not a perfect film. It’s talky in places and not very believable in others. Although the picture is far more than a showcase for Robinson’s talents, it is certainly a reminder of his greatness, elevating the written character to something memorable, a process Robinson repeated time after time during his career.

Film Noir: The Dark Side of Cinema XVII, which includes Black Tuesday, is available now. I’ll review the entire box set soon, but in the meantime, I covered this and other film noir and neo-noir releases in my New Releases video for February 2024.