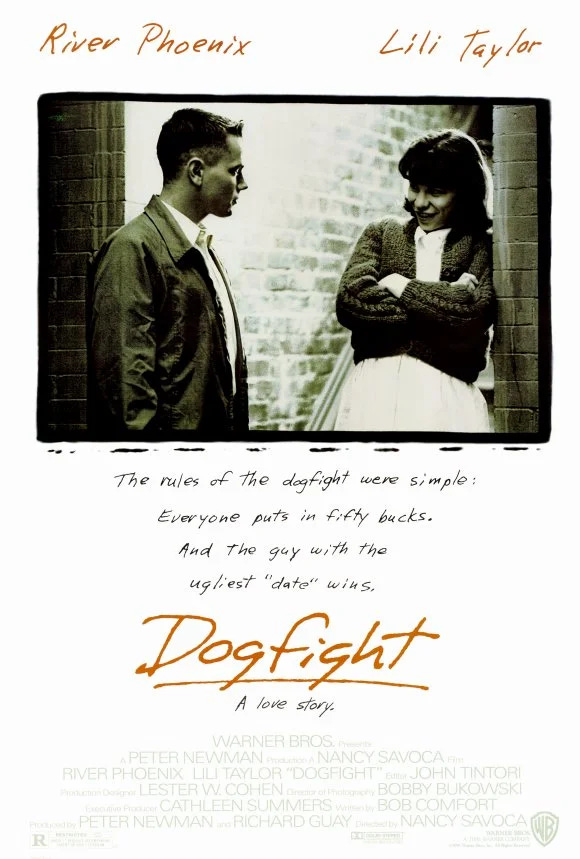

“The rules of the dogfight were simple: Everyone puts in fifty bucks. And the guy with the ugliest ‘date’ wins.”

This text, meant to resemble handwriting, appears on the Dogfight movie poster just below a black-and-white photo of a young couple in the early stages of a relationship. The picture suggests an awkward shyness on the part of the woman and a patient determination from the man. Underneath the title, we find a phrase that confirms our suspicions: “A love story.” You may think you’ve seen this before and know where it’s going, but don’t be so sure.

Most of Dogfight unfolds in 1963 San Francisco, although the time and place may not be immediately apparent to those unfamiliar with the city or the era. This is a very different San Francisco from the one we would know a few years later: 1967’s Summer of Love, an iconic period marked by hippie culture, Haight-Ashbury, drugs, rock, and “free love.” Except for a tiki bar and some neon signs, the colors of this 1963 setting are reserved, the sights and sounds subdued. Yet San Francisco is a port city, so the potential for excitement is always in the air, especially when a group of young Marines arrives in town looking for a night of fun.

Eddie Birdlace (River Phoenix) is one of four Marine buddies on their last night of leave before heading to “a little country called Vietnam,” a place that doesn’t yet mean much to them or most Americans. These guys are prepping for the aforementioned dogfight, as excited as if they were going into battle, and perhaps they are. As was the case for many soldiers in Vietnam, they may be in for some surprises.

Only one of these jokers will walk away from the dogfight with significant cash, and they will all trample some hearts, but the money - to say nothing of the success of their “mission” - is what’s important. When you’re in a battle you aren’t concerned about collateral damage.

To get out of the rain, Eddie walks into a coffee shop where he hears a woman quietly strumming a guitar, singing softly at the back of the shop where most of the customers can’t see or hear her. Moving closer, Eddie discovers the crooning waitress on her break and slowly approaches her. The woman’s back is to the camera, and we can sense from her body language that she’s probably shy and awkward.

She turns around, slightly embarrassed, but Eddie seems oddly delighted: Rose (Lili Taylor) is shy and awkward, her hair a mess, her waitress uniform ill-fitting. She’s perfect for the dogfight.

Upon hearing just a snippet of her song, Eddie tells Rose an unconvincing lie about his knowledge of folk music. Rose knows he’s lying, but he’s a good-looking guy, and he’s talking to her. The shot captures the reflection of cascading rain behind Rose, but when the camera moves to Eddie, he’s standing in front of a portion of the shop that looks vibrant, as if it were painted just moments ago. The positioning of these two characters this early in the film is significant because in a later scene the situation will be very different.

As Eddie works his charm, Rose busies herself, filling a sugar container that’s already full, distrusting herself to make eye contact, and instead looking around to confirm she’s not dreaming. During their introductions, Eddie proves he is who he says he is, showing Rose his military issue ID. Rose examines his picture and says, “Gosh, you look so angry.” Eddie’s response? “I’m not angry. I’m just ready.”

Both statements are lies, which Rose discovers as the “dogfight” (of which she is painfully unaware) unfolds. Eddie’s friends are jerks, caring only for themselves and for getting their kicks, unconcerned with whom they might hurt in the process. Women exist only for men’s pleasure, so there’s no harm done, right? These are the rules of the game, a game much larger than the dogfight.

I will not reveal what happens next, but you know that Rose is eventually going to get wise to what’s going on. I won’t tell you how that plays out, but I will visit another scene that provides a fascinating contrast with the coffee shop meeting.

Eddie and Rose find themselves in a club preparing to close down for the night. With no one else around, Eddie asks Rose to step up onstage and sing something for him. Tentatively she seats herself at the piano, touches the keys a bit, and demurs, yet Eddie encourages her to continue. Softly, but with more confidence than she displayed in the coffee shop, Rose begins to sing the Malvina Reynolds song “What Have They Done to the Rain”:

Just a little rain falling all around,

The grass lifts its head to the heavenly sound,

Just a little rain, just a little rain,

What have they done to the rain?

Just a little boy standing in the rain,

The gentle rain that falls for years.

And the grass is gone,

The boy disappears,

And rain keeps falling like helpless tears,

And what have they done to the rain?

Just a little breeze out of the sky,

The leaves pat their hands as the breeze blows by,

Just a little breeze with some smoke in its eye,

What have they done to the rain?

Just a little boy standing in the rain,

The gentle rain that falls for years.

And the grass is gone,

The boy disappears,

And rain keeps falling like helpless tears,

And what have they done to the rain?

The filmmakers could have chosen many songs from this era, but “What Have They Done to the Rain” is the perfect choice. The lyrics capture the joy and celebration of what Rose hopes will turn into a flourishing and lasting relationship, but they also become a harbinger of corruption. A once good and natural occurrence has turned poisonous, deadly, and devastating. It brings to mind ruined innocence, misplaced trust, and broken promises without a hint of remorse.

This alone would be a potent moment in an already engaging film, but director Nancy Savoca makes some brilliant choices. The camera begins with a tight shot of Rose at the piano, a very personal, very vulnerable shot. She fills the screen even if her voice doesn’t. Yet slowly, as with the song’s lyrics, the camera pulls back to reveal the bigger picture of Rose as a complete person and not just a face.

Both the lyrics and Rose’s delivery of the song work on Eddie as we see him seated at a table in a medium-long shot. There’s a chess board within reach, a symbol of the game he and his buddies have been playing, and he’s smoking a cigarette in a carefree manner. As the camera slowly moves toward Eddie, we see that he understands the lyrics, but more importantly, he sees Rose for the first time, realizing how she is changing him for the better, making him more human, and more caring. River Phoenix was such a gifted actor that he can portray this revelation not only with a look but also in his body language, the way he pulls the cigarette away and stares at this woman with a staggering sense of wonder.

Eddie looks at everything differently now, although something happens near the end of the film - and the Marines’ night out - that makes us wonder if the lessons he learned will stick. Dogfight also shows us that America began to look at everything differently after Vietnam. We still haven’t learned all the lessons we should, but - like Eddie - maybe we’re just beginning to understand that people matter. Everyone should be treated with dignity. Savoca pulls this off in a subtle way, refusing to hit us over the head with it, and Dogfight is more powerful because of it.

Sometimes it takes a Rose (and a tremendous performance from an actor like Lili Taylor) to help us realize that there are people in our lives the world doesn’t deserve. Rose is a heartbreaking character because she exists amid a multitude who see in her nothing more than someone to laugh at or tease. Yet if we listen to her, she works on us, not the way combatants assault one another, but with pure humanity. Rose’s humanity devastates us because we recognize that far too many of us lack it. She is a treasure. So is this film.

Dogfight was released on Blu-ray just a few months ago from Criterion. You can find out more about the release including extras here.