“We’re not going to be separated if we can help it.”

Chicago Calling (1951) is all about being separated from society, work, loved ones, and the truth about ourselves. It’s a movie few people saw upon its release, although many consider it Dan Duryea’s finest performance. If I can convince just one other person to watch the film I’ll count that as a worthwhile venture.

Bill Cannon (Duryea) calls from the window of his ramshackle Los Angeles apartment to his daughter Nancy (Melinda Plowman) playing in the street below. Nancy confesses she got in a fight with a boy who said some nasty things about her parents. “Don’t you and Mommy love each other anymore?” she asks. Bill promises, “We’re not going to be separated if we can help it.”

But Bill’s wife Mary (Mary Anderson) has had enough. Bill, a former photographer, has hit on hard times, reduced to pawning his camera for money, most of which he spends on booze. Ignoring Bill’s promises to change, Mary pawns her wedding ring to pay for a one-way trip for her and Nancy to Baltimore.

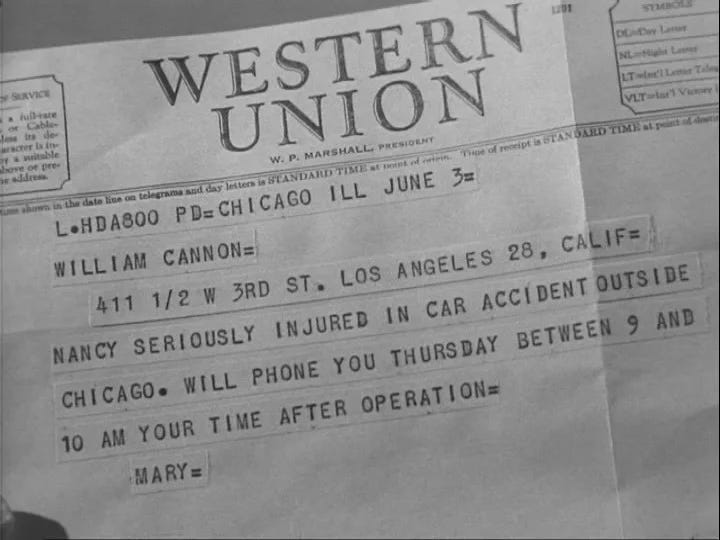

As the days pass, Bill’s life continues to slide. He doesn’t even care when a man arrives to remove the telephone after an unpaid $53 bill. “$53?” the man says. “Whaddya do, call somebody in China?” Just then, Bill receives a telegram: “Nancy seriously injured in car accident outside Chicago. Will phone you Thursday between 9 and 10 am your time after operation. Mary.”

Bill frantically asks everyone he knows to loan him the $53 to get his phone reconnected in time to receive Mary’s call, but his friends also have no money. He needs either a job or a loan, and fast. To make matters worse, Bill’s dog Smitty gets hit by a kid on a bike. Young Bobby (Gordon Gebert), apologizing profusely, is relieved to discover that Smitty’s okay. After talking to Bill for a few minutes, Bobby says he knows where he can get some money. (To put this in context, $53 in 1951 would amount to over ten times as much today, nearly $640.)

Bill learns that Bobby is also in a bad situation, living with an abusive sister (Judy Brubaker) and her equally abusive live-in boyfriend. Bobby is clearly a temporary substitute for Bill’s daughter, who may be recovering or possibly worse. Bill won’t know until he can get his phone fixed, and if that doesn’t happen before Thursday, then what? Yet there’s something in Bobby that Bill can’t resist. Does Bill want to help Bobby, or is Bill more concerned about the money the kid says he can get his hands on?

Bill faces a moral dilemma, a plight that turns critical as time begins to run out. Duryea gives this role everything he’s got. The weariness in his eyes contrasts with his love for Nancy, although she’s not here and Bobby is. We hear the desperation in Bill’s voice, pleading with a construction foreman to give him work even while Bill is inappropriately dressed, wearing a suit. It’s excruciating watching Bill wear himself out on a demolition site, but he keeps at it. Even in this photo from the film, you can see the foreman standing above Bill in a power position, with Bill practically surrounded by the rubble, looking up to the only man who can save him.

His performance as Bill Cannon may be Duryea’s finest moment in a career filled with superb performances, yet most audiences didn’t respond favorably when the film was released. Throughout his career, Duryea was constantly trying to balance his shifty villainous roles with parts that audiences would find sympathetic, more in line with Duryea’s real life as a dedicated family man who shunned the Hollywood lifestyle, preferring to spend his free time with his family and doing charitable work. He felt so strongly about this role that he accepted a percentage of the film’s gross instead of a salary or flat fee, which turned out to be a huge mistake when the film did not perform well.

I became fascinated with the character of Bill Cannon. He seems lost without his camera to help him interpret the world around him. We aren’t sure how much of this lost feeling occurred before or after he pawned his camera, but he seems to recognize something of the moral standard he’s drifted away from with his drinking and lack of drive to find work. Then he learns that his daughter’s life may be at stake.

Bobby’s genuine sorrow over hitting Smitty resonates with Bill, perhaps because he recognizes something good in Bobby or something Bill himself has lost. Maybe Bobby’s presence convinces Bill that he’s acted childishly with his grown-up responsibilities. Regardless, Bill has made a true connection, something difficult to find in the downtrodden section of Los Angeles where Bill lives, a location that often looks like postwar Europe and could realistically pass for some of the “rubble noir” movies from overseas. This relationship between Bill and Bobby works well, not only due to Duryea’s bravura performance, but also because of the extraordinary acting by Gordon Gebert (still with us at age 82), who also impressed audiences in The Narrow Margin (1952), Holiday Affair (1949), and The Flame and the Arrow (1950). These two guys could easily have had their own TV show that would’ve blown The Courtship of Eddie’s Father out of the water.

Chicago Calling has been called “the American Bicycle Thieves” and its sense of neo-realism is strong, even though the film’s finale leaves us with a softer touch than I would’ve liked. The gritty realistic nature of the picture, combined with several moments of pure humanity, may cause some to categorize it as a drama (or melodrama) rather than a noir. Yet regardless of how you label it, Chicago Calling is a must-see.

The movie is available to stream via a somewhat questionable streaming platform (I’ll let you Google it) and on DVD from Warner Archive.