(This post is modified from a previous entry from my former website.)

“You know, Mac, sometimes I feel like I don’t know what it’s all about anymore.” - Roy Earle

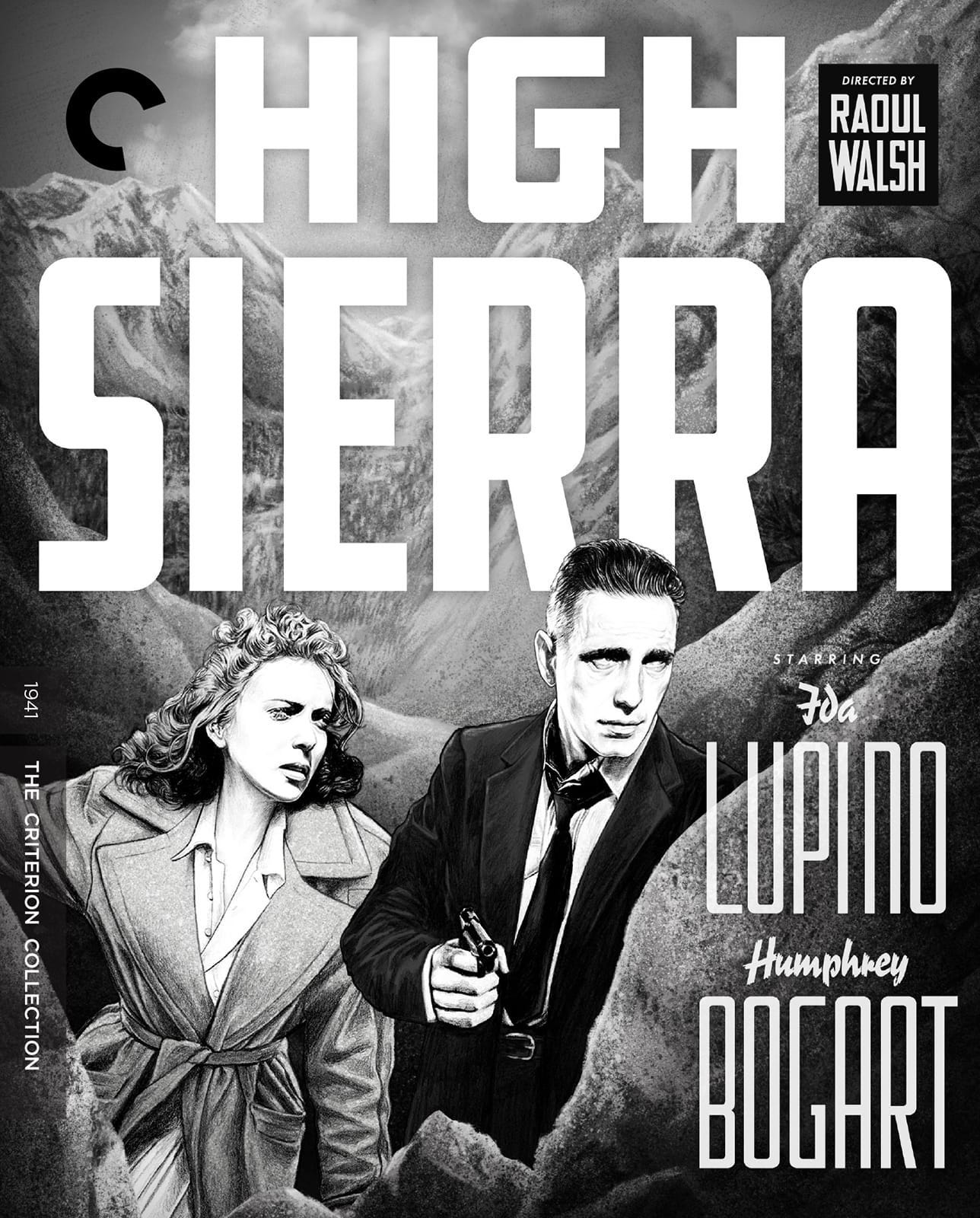

It may be true that The Petrified Forest (1936) launched Humphrey Bogart’s career, but High Sierra (1941) made him a star. High Sierra’s Roy Earle is a much more complex character than Duke Mantee, and Bogart’s acting chops had developed significantly during the five years between roles. While High Sierra lifted Bogart to the upper tier of leading men, the film also signaled the demise of the gangster picture, a genre that had seemingly endless staying power in the 1930s.

On the surface, High Sierra is a heist-gone-wrong film (although how many heists in films ever go right?), but what is happening is far more interesting and significant. Bank robber Earle has just been released from prison after being pardoned by the governor of Indiana (for reasons I’ll leave for the viewer to discover) and quickly formulates plans for one last heist. Earle is a legend, although an aging one, and early on, we see that the years have left him both jaded and unsentimental.

Earle’s two new accomplices, Red (Arthur Kennedy) and Babe (Alan Curtis) are green and stupid, unlike the guys Earle worked with in the good old days. Plus, the new men have picked up a woman named Marie (Ida Lupino), and women, says Earle, always spell trouble when planning a job.

Further complications occur when Earle, a former farm boy, meets the Goodhues, a family of failed farmers led by the good-natured Pa (Henry Travers). Earle feels for them and their predicament but is taken with Pa’s granddaughter Velma (Joan Leslie), a beautiful girl with a clubbed foot, which Earle believes could - and should - be corrected.

An inevitable atmosphere of tragedy is written all over this film yet never overpowers it, even when you think the appearance of a cute little dog named Pard (Bogart’s dog, Zero) will burden the film with unnecessary sentimentality. (Although one character does get quite weepy, bordering on excess, as we near the end.)

High Sierra is a rich and complex film, primarily due to Earle’s well-developed character. Bogart balances the hard-edged criminal with a softness that’s never forced or sappy. Anyone doubting Bogart’s acting ability should watch the scene in which Earle visits Velma after her operation. Bogart’s range and control here are remarkable. I wasn’t around in 1941, but I’m sure those audiences had no idea Bogart could pull off such a moment.

Although High Sierra is more a crime picture than a film noir (and an early one at that), it contains an inevitability that belongs to noir. Earle has tasted both the criminal life and that of law-abiding people, and although he’s on the outside, he’s still imprisoned, not only by his crimes but also by emotions he doesn’t know how to deal with. He’s not free, but he’s found a new landscape that allows him to leave the gangster community behind. Yet it’s a land with no room for him; he’s like a sideshow attraction, which is reflected in the circus atmosphere of the last 10 minutes of the film. Earle’s is a life with unfulfilled loves, and even while he’s trying to figure this world out, he knows it’s a world he’ll never be able to embrace fully.

A wonderful scene conveys this notion as Earle takes Velma outside one night to look at the stars. In any other film, this moment might foreshadow the beginning of a romance, but here, it serves as a reminder that a life of normalcy for a career criminal like Earle is as distant as the heavens. The outdoor setting also serves as a fitting stage for the film’s ending. Shot on location in the Sierra Nevada Mountains (when location work was not all that common), the grandness of the open spaces during full daylight is too much for a man who’s lived much of his life enclosed in shadows of concrete and steel. The screenplay, Tony Gaudio’s gorgeous cinematography, and Walsh’s expert direction combine to make the ending powerful and unforgettable.

The novel by W.R. Burnett (who also wrote Little Caesar, whose film version made Edward G. Robinson a household name in 1931) was championed by John Huston, who got to know and appreciate Bogart on the set of High Sierra. And although Ida Lupino’s name appears onscreen first, this was the last time Bogart would receive anything less than top billing.

The Criterion Blu-ray (released in 2021) looks spectacular and also includes Colorado Territory (1949), something of a remake of High Sierra, also directed by Raoul Walsh.