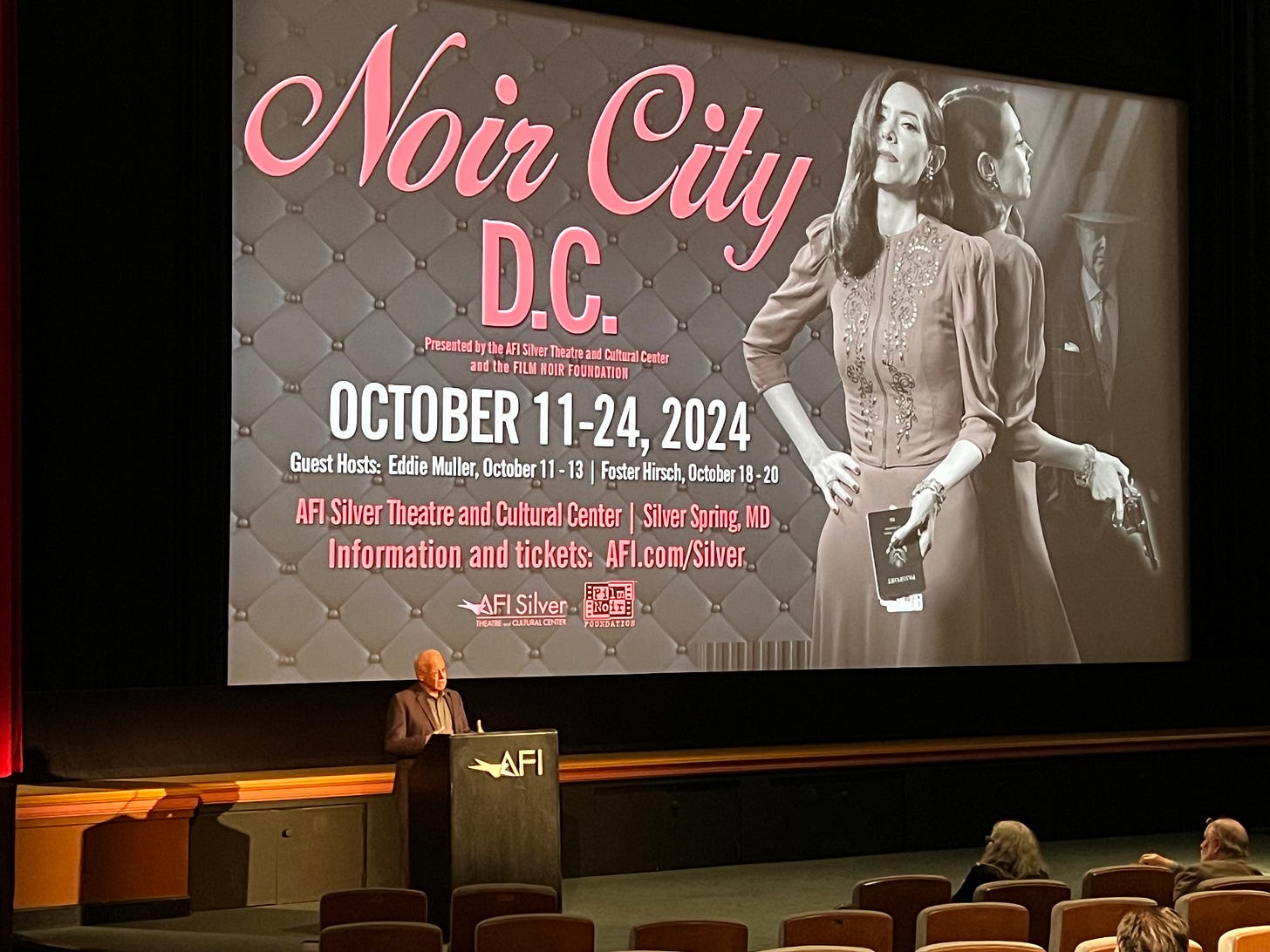

Noir City DC Part Two

My second day at the festival, this time with Foster Hirsch navigating the journey

As Foster Hirsch pointed out in his introduction, although La Bête humaine was released in 1938 before the recognized beginning of the noir era, the movie is pure film noir with perfectly realized noir motifs, including “naturalism with a heavy dose of fatalism,” a concept that went against the grain of director Jean Renoir (son of artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir). Renoir was a humanist who had faith in human nature, an attribute that is nowhere to be found in La Bête humaine.

Right from the start, the film gives us visual clues about the character of Jacques Lantier (Jean Gabin), a train engine driver. The high energy of the train’s movement combined with Lantier’s passion and desire to see it run powerfully merge, giving the audience a sense of predestination and danger.

Simone Simon (who, four years later, would star in Cat People) plays Séverine, whose husband, Roubaud (Fernand Ledoux), the stationmaster, accuses Séverine of infidelity and plans to solve the situation with murder. Lantier gets involved in more ways than one; yet we see early in the film that he has his own issues.

Renoir wasn’t going for realism but expressionism. In watching the film, it’s important to keep in mind that France was about to be overtaken by the Nazis just one year later.

Although La Bête humaine enjoys a higher reputation, Hirsch commented that its remake, Human Desire (1954), should not be dismissed. (He originally saw Human Desire during its initial run as the second feature behind The Silver Chalice. Wow…) Hirsch stated, “I recognized that the film…had something to it,” commenting that Gloria Grahame and Simone Simon “were not that far apart.” But comparing Glenn Ford and Jean Gabin? Hirsch declares, “Ford can’t touch him.”

Glenn Ford is Jeff Warren, an Army veteran train engineer who gets mixed up with Vicki (Gloria Grahame) and her murdering husband, Carl (Broderick Crawford). Train metaphors abound, and they’re fairly effective. Grahame is excellent in the film, yet she overshadows Crawford, who also does fine work here. Some consider this a “throwaway” effort from director Fritz Lang, but I’d argue that such is not the case. Hirsch commented on Fritz Lang, “There’s no trace of humanity in his bones.”

That’s probably true, yet the Production Code would not allow the director to present the picture as darkly as Renoir did with La Bête humaine. You could say both directors went against type in these two films. I prefer Renoir’s vision, but Human Desire should be talked about more than it is today.

Earlier this year, Hirsch was assigned to present Zero Focus (1961), a film he’d never seen, at a few Noir City festivals. He confessed, “I saw it three times before I could get a handle on the plot. It’s the most convoluted plot I’ve ever seen. You can’t be inattentive for one moment. I’ll do my best to explain.”

Although the scenes are long, the cutting is abrupt, especially for a film from 1961. Not only does the movie present flashbacks, but flashbacks within flashbacks, and some from the point of view of an unreliable narrator. Hirsch mentioned, “It feels like you need to be good at geometry to watch this film.”

Zero Focus follows Teiko (Yoshiko Kuga, Cruel Gun Story, Drunken Angel), whose husband Kenichi (Kōji Nanbara, Branded to Kill, The Bad Sleep Well) goes on a short business trip just days after their marriage and never returns. Desperate to find out what happened to Kenichi, Teiko travels through Japan hoping to discover his whereabouts but instead, she finds things about her husband she’d rather not know. Takashi Kawamata’s cinematography is stunning. If you ever have a chance to see Zero Focus, jump on it.

Like Zero Focus, Across the Bridge (1957) also deals with identity: someone attempting to become someone else. More popular in the UK than in the U.S., this British picture directed by Ken Annakin stars Rod Steiger as Carl Schaffner, a German-born businessman living and working in England. After being caught stealing his company’s funds, Schaffner flees to Mexico. While traveling by train, Schaffner finds a man with a physique and appearance close to his own, disables him, and assumes his identity. Yet Schaffner discovers the man whose identity he’s chosen is wanted for murder in Mexico. Although the premise seems unlikely, the tension is superb.

When asked about his all-time favorite film roles, Steiger usually mentioned The Pawnbroker (1964) and this film. As Hirsch points out, Steiger “could be a terrific ham,” yet he’s excellent in Across the Bridge.

But I believe Steiger is outacted by Delores the dog, who gives one of cinema’s great dog performances. Also stepping up his game is director Annakin, whose filmography (except for The Longest Day) consists mostly of unremarkable films. Across the Bridge is worth seeking out.

More for your Noirvember coming up soon!