Noirvember 2024: A Dana Andrews Double Feature

Although I haven’t yet written about them, I’ve recently watched double features with Valentina Cortese, Robert Mitchum, and now, Dana Andrews.

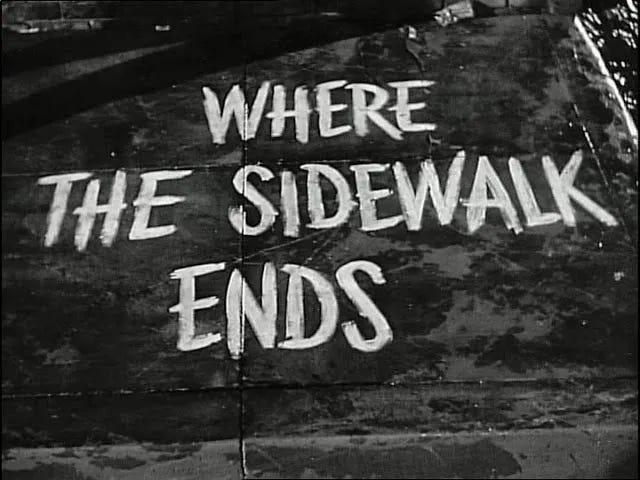

Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950) Otto Preminger

While New York City’s 16th Precinct welcomes a new commander, Detective Lieutenant Thomas (Karl Malden), Detective Mark Dixon (Dana Andrews) isn’t exactly in a celebratory mood. Dixon’s superior, Inspector Foley (Robert Simon), reminds Dixon that while he and Thomas arrived on the force at the same time, Dixon’s career has been riddled with complaints of police brutality. “Your job is to detect criminals,” Foley tells him, “not to punish them.”

Cut to an illegal crap game where a gambler named Paine (Craig Stevens) beats a Texas high-roller (Harry von Zell) to death, then flees the scene. Dixon takes the case, tracks Paine down, and accidentally kills him while Paine resists arrest. In one of the film’s most gripping scenes, Dixon has seconds to decide whether he’ll admit the truth or cover up the accident. Of course, we know what he’s going to do...

Not only does Dixon have to clean up what he’s done, but he also has to investigate the original case, which makes for an interesting plot twist. To ratchet things up even tighter, Dixon begins to fall for Paine’s wife, Morgan (Gene Tierney), but he certainly can’t tell her the truth about what happened to her husband.

Although brief, the famous opening title credits on the sidewalk soon give way to the place where the sidewalk literally ends, as we notice bits of trash falling into the sewer, a metaphor for what happens when someone steps out of bounds and descends into darkness. One of the great themes of film noir is the idea of the city and its corruption seeping into a character’s being, filling his or her soul with an inevitable and fatalistic blackness. Andrews gives a superb performance, often without saying a word, allowing his eyes to react to every word, idea, and theory offered to him. One of cinema’s weaknesses compared to prose is that you can’t know (aside from voice-over narration) what a character is thinking, yet by watching Andrews, we come close to understanding each thought flashing through his head.

Ben Hecht’s superb screenplay withholds an essential piece of information until we need it. It’s a bit of knowledge that explains much and, in the hands of a lesser screenwriter it would’ve been presented too early and too often. By keeping that card close to the vest, Where the Sidewalk Ends allows the viewer to delve into the troubled psyche of Dixon’s soul, exploring the darkness of a character who struggles to do the right thing.

Although the film was released in 1950, in what’s generally considered the second half of the classic film noir era, one scene represents a theme that would later appear in many neo-noir films of the '60s, '70s, and beyond. It’s a brief moment, lasting maybe two seconds, but it helps define neo-noir. At the crap game, Payne and the Texas high-roller are fighting. The room is filled with other men, yet none are cheering, jeering, chanting, or doing anything but watching in silence. This isn’t the first time we’ve seen silent onlookers in a fight in film noir, but the expressions on the faces of the observers seem to convey a “This is how it is” attitude. There’s no emotional connection, no sense of either regret or enjoyment. It’s simply noir.

Where the Sidewalk Ends is one of those films that works so well visually, and one reason is that director Otto Preminger doesn’t call attention to his direction. There’s nothing fancy going on here, but each shot places his characters in exactly the right place spatially to fit each scene’s mood. For example, Lieutenant Thomas questions Morgan in one scene with Dixon standing in the middle. Dixon is literally caught in the middle of this and other moments, having to listen to and not react to Thomas’s questions and Morgan’s answers. Again, Dana Andrews’s eye movements crank up the tension and are worth the price of admission.

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956) Fritz Lang

Fritz Lang’s last American film follows novelist Tom Garrett (Dana Andrews), a man looking to get the inside scoop on capital punishment for his next book. Garrett’s future father-in-law, newspaper publisher Austin Spencer (Sidney Blackmer, left), a vocal opponent of capital punishment, proposes an idea. No one, including Spencer’s daughter Susan (Joan Fontaine), can be trusted with any aspect of the project, so it’s just between the two men.

As luck would have it, the police have a recent unsolved crime they’re investigating: the killing of a young showgirl. The plan? Plant (and carefully document) fake evidence connecting Garrett to the crime, get convicted, and then discredit the system by showing Garrett’s innocence. What better way to expose the problems related to the death penalty? But this is film noir, so we know something’s going to go wrong, very wrong.

Many things go wrong with this film. As David Hogan points out in his book Film Noir FAQ (2013), director Fritz Lang seemed to be going through the motions with “the dull competence of a mid-‘50s television drama.” I can’t argue with him. As Hogan also mentions, it’s hard to believe this is the same Fritz Lang who directed The Big Heat three years earlier. Lang’s visual mastery is all but absent here, further damaged by shoddy production values.

I’m willing to overlook the film’s ridiculous premise, but the Douglas Morrow story and screenplay keep adding one absurdity after another. Yet, as Eddie Muller states in his Noir Alley outro for the film, the ending is gutsy, “a spit in the eye of the prevailing ‘happily ever after’ normalcy of the 1950s.” Be sure to watch Eddie’s outro after you’ve seen the film. You’ll find out one reason why this film may have hit too close to home for Lang.

Take a look at Letterboxd, and you’ll see a wide range of reviews and opinions, joining those of critics who despise the picture and others who consider it Lang’s greatest film. It was also his final American movie. Lang returned to Europe where he continued to make films for a few more years.

The stories of Dana Andrews’s drinking problems are legion, and the actor frustrated Lang constantly during the production, yet I consider Andrews one of the most solid actors of the classic Hollywood era, especially in film noir pictures. I don’t care if he was drunk, sober, or picking up signals from Jupiter, he’s fantastic in his delivery and even better at silently reacting, letting his eyes do the work.

Whether you’re watching double features of actors, directors, and cinematographers or simply enjoying film noir with no definite plan, I hope you enjoy the rest of Noirvember. There’s lots of darkness and mayhem to go…

Thanks for the reviews, curious to watch both of these.