The Hitch-Hiker (1953) Ida Lupino

Or, with all due respect to Lawrence Tierney, The Devil Thumbs a Ride

(This article is modified from a previous entry from my former website.)

Let’s admit it, we all love villains. Just think of the different synonyms for a villain: scoundrel, reprobate, cur, miscreant, rogue, louse, brute, renegade, and the king of them all – devil. Yet there’s one thing that no villain can live without: a hero to oppose him. So, if we have a villain and a hero, we must also have a story. That story usually pits a hero we can root for against a villain, someone so opposite from the hero that he (or she) is immediately recognizable as such. How disconcerting to discover the villain may resemble us. This disturbing realization lies at the heart of Ida Lupino’s The Hitch-Hiker, brought about through its villain, Emmett Myers.

The film opens with buddies Roy Collins (Edmond O’Brien) and Gil Bowen (Frank Lovejoy) headed to Mexico for a fishing trip, two pals planning to enjoy some harmless fun while leaving their wives (and family, in Bowen’s case) at home. Once they cross the border, Roy wonders whether a woman named Floribel, whom they’d met years earlier, is still a regular at a local Mexicali club. We can’t help but wonder if this could be Roy’s primary motivation for the trip, maybe not for Floribel in particular, but some potential shenanigans with the opposite sex. Gil replies that so many years have passed, Floribel’s probably dead. Gil further states that this trip marks the first time other than the war (undoubtedly referring to the Korean War) that he’s been away from his wife and kids. Roy understands; he’s got a wife of his own but still wants to recapture some of those wild bachelor days.

When they pull up to a different nightclub, Roy can’t wait to see an advertised performer named Juanita and her famous fan dance, but Gil sits in the passenger seat asleep… Until he stealthily opens one eye to see that Roy has driven them away from the club. (Gil’s secretly open eye provides an eerie link to the killer’s eye later in the film, implying they might share a connection.)

Roy and Gil soon stop to pick up a hitchhiker (William Talman), a man we’ve seen up until now only partially (usually only his legs and feet) after he’s ended the lives of others who’ve made the regrettable decision to stop for him. As he enters the back seat of Roy’s car, we see the dashboard lights reflected onto the faces of Roy and Gil, but the hitchhiker remains in shadow. But not for long.

“Sure, I’m Emmett Myers,” the hitchhiker says as he leans forward into the light, pointing a gun at the men. “Do what I tell you and don’t make no fast moves or a lot of dead heroes back there get nervous.” Myers keeps spouting orders, instructing Roy and Gil on how they’ll get out of the car from this point onward.

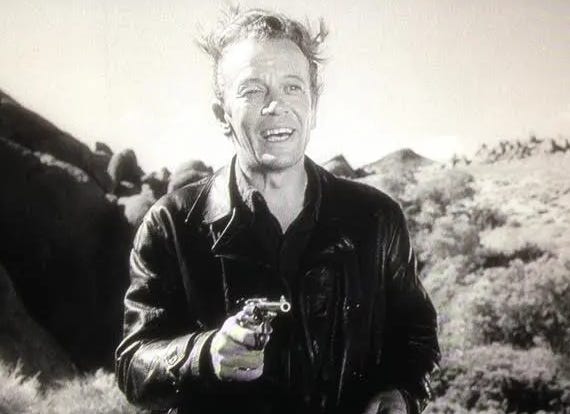

During one close-up, we get a hint of Myers’s eye condition. His right eye is half-closed, while his left is full open, wild-eyed, like some grotesque demon. In this shot, you can’t escape the feeling that this man is dual-natured: a normal human nature struggling with a twisted, psychotic, possibly even demonic nature. Myers is linked to the devil in several ways. In an early scene (perhaps accidentally, but I doubt it), we see him standing in the open desert, his gun pointed at Gil and Roy. The wind blows just enough to lift Myers’s unkempt hair on both sides of his head, giving the appearance of devil horns. Later on a radio broadcast, an announcer states, “Yesterday the devil found another ride,” before describing Myers’s latest getaway.

Further adding to the devil connection, Myers tells the men during their first night together, “I know what you’re thinking, Collins. You haven’t got a chance. You guys are gonna die, that’s all. It’s just a question of when.” It’s almost like the devil is reminding them of their mortal existence, something we all know but don’t like to acknowledge. Myers almost seems supernatural with his partially paralyzed eye. “You couldn’t tell if I was awake or asleep. I have one bum eye. Won’t stay closed. Pretty good, huh?” Not only is Myers’s eye creepy, but it carries an otherworldly omnipresence, suggesting that this devil is omniscient, always seeing everything. It’s a simple device, but one of the most unnerving moments in the film.

Myers even taunts Roy and Gil in an accusatory, devil-like fashion after finding out the men told their wives they were going one place, then somewhere else. Myers gloats, standing above the helpless men “And then you came to Mexico. What for? Dames? You guys ought to be ashamed of yourselves, causing all that trouble, telling lies. They got everybody and his brother looking for you in them mountains,” suggesting that there’s a price to be paid for their intentions, even if they didn’t get to carry them out. There’s also a slight suggestion that Myers could be the punishment for those intentions, but the more lethal implication is that the men are closer to Myers than they think.

These scenes and the implication that man is a dual-natured being force us to examine ourselves. We certainly don’t want to be identified with Emmett Myers in any way. (Hopefully, we haven’t killed anyone or even held a gun on someone trying to help us.) The idea also forces us to make moral comparisons and judgments. Sure, guys might lie to their wives about where they’re going on a “guys only” vacation, but is that on the same level as killing people? Of course not, but I think we would all agree that lying and murder are both wrong. But does the fact that Gil and Roy lied to their wives bring them closer to the level of Myers? Are we in any way capable of becoming an Emmett Myers? Lying and murder are both wrong, but they’re worlds apart, right?

Let’s leave those questions hanging for now. What about our villain? What does he want? One thing he wants is power. We see this in how often Myers looks down on Roy and Gil, whether from the hood of Roy’s car, an outcrop of rocks, or some other elevated position. Myers has to do something to elevate himself when it’s obvious he’s inferior to these two men. At one point, Myers makes Gil look up Santa Rosalia on a map, either because Myers can’t read a map or just plain can’t read. He also can’t understand Spanish and insists on dealing only with people who can speak English. In every case and every scene, Myers holds a gun, which is the only way ignorance can wield power.

Myers also sees himself as superior to Roy and Gil in that he has (in his mind) obtained a sense of wisdom they never discovered. “You guys are soft,” Myers sneers. “You know what makes you that way? You’re up to your neck in IOUs. You’re suckers! You’re scared to get out on your own. You’ve always had it good, so you’re soft. Well, not me! Nobody ever gave me anything, so I don’t owe nobody.” It’s almost as if Myers is taunting them, telling them that if they weren’t so “soft,” they could be just like him (as if they’d want to). The connection is pulled even tighter when Myers insists that Roy change clothes with him so that the authorities (should they encounter them) will mistake Roy for him. Again, Myers hints that on a fundamental level, they’re not so far apart, that he has the life they wish they could have, one of complete freedom. Yet the problem is that Myers can never be free.

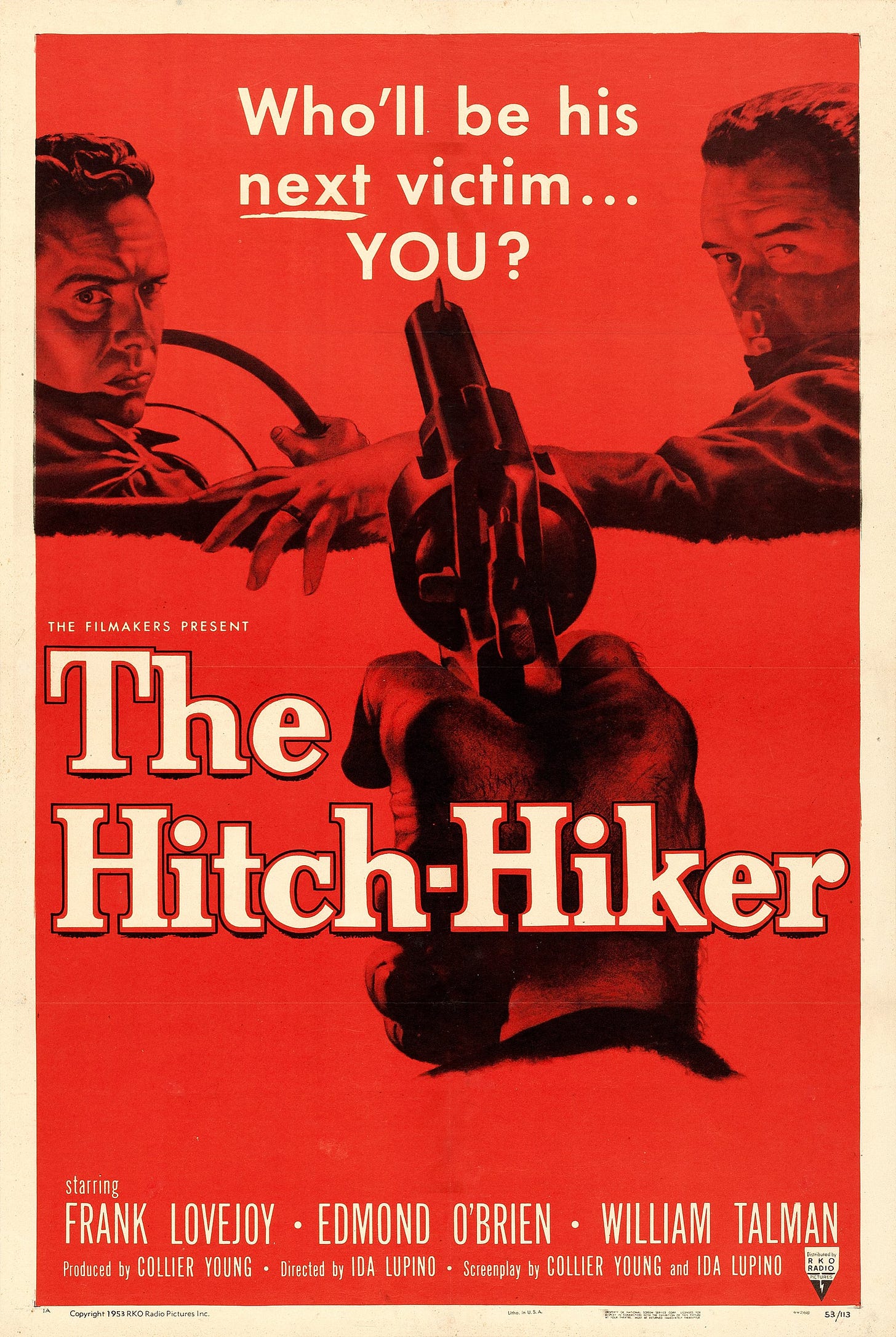

We seem to be in danger of complicity with Myers from the movie’s poster, which asks, “Who’ll be his next victim… You?” We hope not, but maybe we should think of ourselves differently. Edmond O’Brien and Frank Lovejoy are turned around, looking at us through the poster as if we’re holding the gun aimed at them. Are we complicit? Are we Myers, or are we capable, even in a remote way, of becoming Myers? It seems unthinkable. We’re nothing like this guy, right?

Yet Roy starts to become like Myers in some ways, thinking he really is soft and needs to prove himself, taking his justified anger out by fighting back. Gill is more level-headed, insisting that they bide their time. Roy’s humanity begins to break down, but Gil is solid, patient. As a draftsman, Gil is used to being given specific orders. As a mechanic owning a garage, Roy is in control at work. Every decision is his. He can’t stand for someone else to be in charge. Gil is practical, patiently waiting for things to play out. He, after all, has a wife and daughter at home, and Roy’s willingness to mingle a little too much with the ladies indicates that his relationship with his wife, perhaps, isn’t very strong or important to him.

Whether we think of Emmett Myers as a type of devil or as a normal person gone wrong through a series of misfortunes, bad breaks, or flat-out psychotic behavior, he’s a frightening character, and Talman’s performance is one of the most effective in all of cinematic villainy. So be careful out there. Keep your eyes (both of them) wide open, don’t tell lies, and for the love of all that’s holy, don’t stop for that guy on the side of the road.

Next time, I’ll have more on director Ida Lupino and her career. Thanks for reading.

If you enjoy this post, I hope you’ll check out my other articles, and please feel free to share this article.