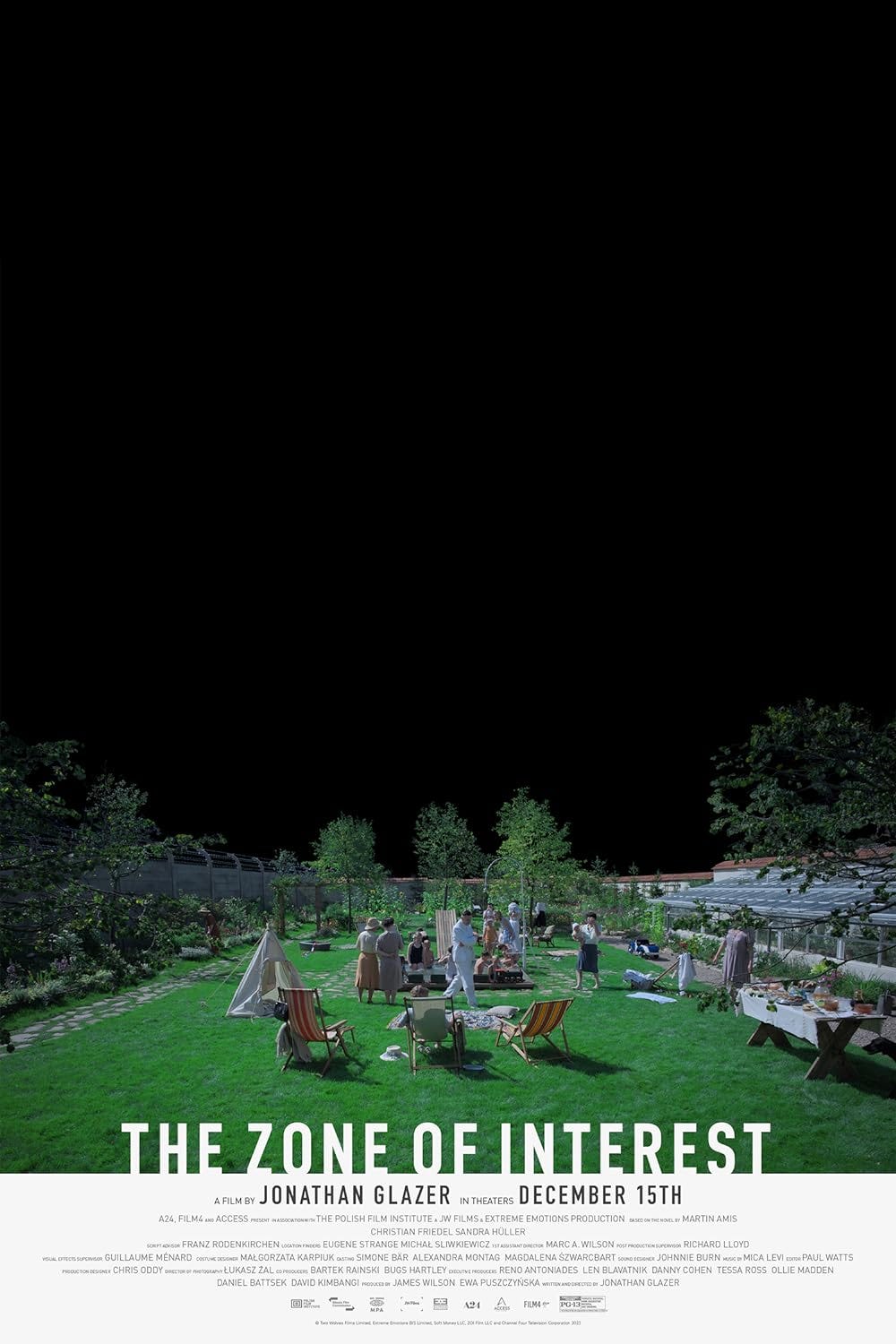

The Zone of Interest (2023): A Review

Are you listening?

The Zone of Interest is a Holocaust film that includes neither visual graphic violence nor torture, but its power will haunt you both during the movie and after its conclusion. In director Jonathan Glazer’s hands the old writer’s adage “Show, don’t tell” becomes “Listen, don’t watch.”

Clinical professor, author, and speaker Scott Galloway states in a recent article:

We hear 20 to 100 times faster than we see, and what we hear stays in our heads longer, often evoking strong emotions… We all hear things; there’s no corner of the globe that’s free from the vibrations that manifest in sound. So we must decide what to listen to. But many of us aren’t listening, and that dampens our abilities and undermines our relationships.

Taking liberties from the 2014 novel by Martin Amis, The Zone of Interest follows Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland during World War II. Höss, his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), and their children live outside the camp in a picturesque home surrounded by a massive yard, a modest pool, and towering walls. The walls must be high to prevent the Höss family from witnessing the atrocities occurring literally in their own backyard.

Although the family (and the audience) cannot see the nearby horrors, they can hear them: the screams, the gunshots, the sounds of the crematorium at work. These aural reminders of death occur throughout each day. Yet the family reacts as if they’re living in another world because they are. They have chosen what they will listen to.

Hedwig’s daily routine consists of entertaining guests, running the house, keeping the servants in line, and occasionally caring for the children as well as relaxing and luxuriating in the idyllic setting. If we didn’t know better, we would guess from Hedwig’s actions that she has no idea of the savagery occurring next door. But she does, as is evidenced by her conversations with friends and visitors.

We’re soon aware that Hedwig is self-absorbed, setting herself up as the queen of this domestic castle, a position she will never willingly give up, even if something were to happen to Rudolf. She’s not uncomfortable living next door to the concentration camp; rather, she thrives on it. Not only can she ignore the screams and cries from nearby, but she often ignores the same from her own baby. When Hedwig’s mother Linna (Imogen Kogge) comes to visit, she is initially impressed with the home until the sounds of death and the nighttime fires from the crematorium prevent her from sleeping.

What about Rudolf? When the commandant is not at home enjoying his house and children, he’s meeting with Nazi officials or seeking the advice of those who can help him with an efficiency problem. In one scene two men sit down with Höss and show him a diagram depicting several stations of a crematorium. These men explain how their system of distancing ovens far enough away from areas where ashes can be stored, then rotating those stations, is more efficient than their current method. Another conversation involves how a revamped train schedule will allow for a greater number of prisoners to be transported to the camp. These men could be talking about moving and disseminating goods or material, but we know they’re speaking of something else. In their minds, this is nothing more than a supply chain problem.

Yet Rudolf seems conscious of cleansing himself and his children from the truth. At home he is constantly putting everything in order through a nightly routine of checking the condition of each room. Other moments convey even greater urgency. In one scene he and his children are swimming in a river just outside their house when Rudolf discovers evidence of human remains touching his legs, prompting him to quickly order the kids out of the water. There are some things you simply can’t ignore.

The act of suppressing information is something we all do at one time or another. When we were children, our parents may have told us “Don’t look” while driving past a horrible traffic accident, or perhaps they covered our eyes during a scary scene from a movie. As adults, we generally know what we can’t handle (for me it’s watching an actual surgical procedure) and respond by averting our eyes. This may even happen when we view films with frightening or disturbing imagery.

No doubt we have all heard of or experienced either temporary or permanent loss of one of our senses, a condition often resulting in the strengthening of other senses. If this is indeed the case, Rudolf and Hedwig have not only walled themselves away from the visual horrors next door but have dealt with their heightened awareness of the aural terrors by suppressing them. This isn’t a one-time act but a constant one. They have trained themselves, first by denial, then acceptance. But if Scott Galloway is correct, it is impossible to escape the vibrations of sound. Even if you can’t hear in terms of volume, you can often feel reverberations in the same way deaf individuals can feel the vibrations of sound and music. Imagine the difficulty of consistently suppressing what you can feel and maintaining that suppression for hours, days, weeks, months. Yet Rudolf and Hedwig have succeeded in doing so. Or at least they think they have.

One of the aspects of The Zone of Interest that proves so unsettling is the recognition that perhaps we are suppressing what our senses are telling us. We may not be living contented lives in an idyllic setting while people are being tortured to death next door, but it’s certainly possible that we’re ignoring other situations: a coworker being verbally abused by her boss, a senior adult living nearby who needs help, or a hundred other examples. Suppression can stifle compassion. Consistent suppression can kill it.

German critic Hanns-Georg Rodek, writing for Worldcrunch, notes, “Glazer describes the situation in what is possibly more oppressive than anything we’ve seen in Holocaust films before. It concentrates in one garden the attitude of an entire nation that wanted to know nothing.”

The film is horrific because of what we don’t see. We may think that Glazer’s decision not to show us visually what’s going on next door is a blessing. It’s not. Because of this decision, The Zone of Interest sticks with you longer than most visual representations of horror we’ve seen in other Holocaust films, and the passage of time in the movie (only 105 minutes) allows this anxiety and unease to build until we can’t take it anymore. I found myself longing to escape from this film and its characters.

Some critics have suggested that The Zone of Interest is, in fact, two films: the visual and the aural. The contrast is always present, even when Glazer utilizes night vision scenes of a girl secretly hiding food for prisoners to discover. Ironically these nighttime moments convey the movie’s only light of hope, a quiet form of resistance, while the Mica Levi soundtrack underscores the danger this girl is inviting. (This article goes into more detail involving these scenes and how they were inspired by a true story.)

As you watch the film you realize that the project could have gone off the rails in so many ways. Yet, Glazer is in complete control of the movie’s balance, tone, pacing, and overall composition from its opening to the film’s ending, which offers a powerful touch that I won’t disclose here.

The questions we ask during the film may progress from “What were these people thinking?” to “Why does this keep happening?” We might even ask, “How much of these sounds of suffering could I withstand, and for how long?” Yet perhaps Glazer’s focus lies in showing us that man’s inhumanity to man happens gradually and that, for some, if we can’t see the atrocities, we can’t be responsible for them. May we never be found guilty of that sin.

Glazer’s previous films avoid the tropes that normally accompany their respective genres: Sexy Beast (2000), a crime film; Birth (2004), a paranormal/psychological drama; and Under the Skin (2013), a science fiction story. All of these films, at least on some level, disrupt our assumptions of what certain genres or categories of film should conform to for them to be satisfying. When our expectations are challenged, we’re frequently either disappointed or uncomfortable (or perhaps both).

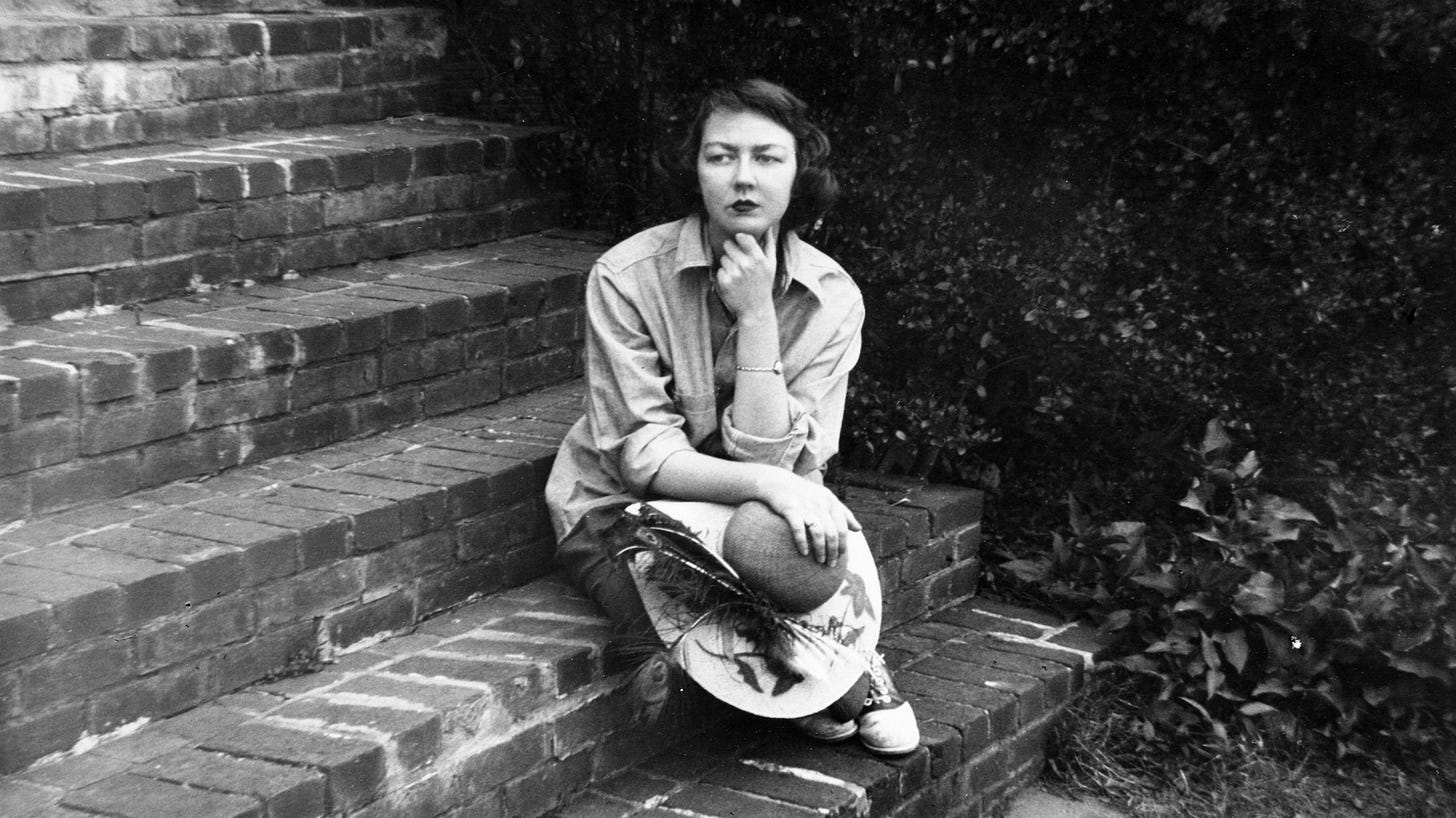

I am reminded of a quote from Flannery O’Connor, a devout Catholic writer quoted from Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose:

When you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock -- to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.

Many reading O’Connor’s work (particularly her short fiction in the collection A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories) recoil against the unpleasantness, the grotesque characters, and the shocking nature of what some people will do to each other. But sometimes we need to have our faces pushed into the truth of what’s going on around us. Rather than suppressing, we may need to look deeply into the abyss in all its ugliness to experience the reality of injustice and inhumanity. When we’re unsettled, we have the choice of asking ourselves some hard questions. “Why is this happening? How did this happen? What should I do about this?”

Or we can pretend the ugliness doesn’t exist. Perhaps worse, we can redefine it.

The Zone of Interest is not a typical Holocaust picture. Glazer has upended our expectations and given us a film we must either deal with or ignore. May we not choose the latter.

The Zone of Interest has been nominated for five Oscars: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay (Glazer), Best International Feature, and Best Sound (Tarn Willers and Johnnie Burn). At the recent BAFTA Film Awards, The Zone of Interest won for Outstanding British Film, Film Not in the English Language, and Sound.