Sometimes you just want to see something different, perhaps a film that may surprise you. It could be a movie you never knew existed from a place or culture you don’t understand. Due to the efforts of Eddie Muller, the Film Noir Foundation, and many others, noir fans are discovering that the heyday of film noir was not confined to America. It was, and still is, a global phenomenon. Noir and its themes are universal, and even if we don’t recognize the actors, locations, or languages of these films, they often contain treasures we never dreamed of.

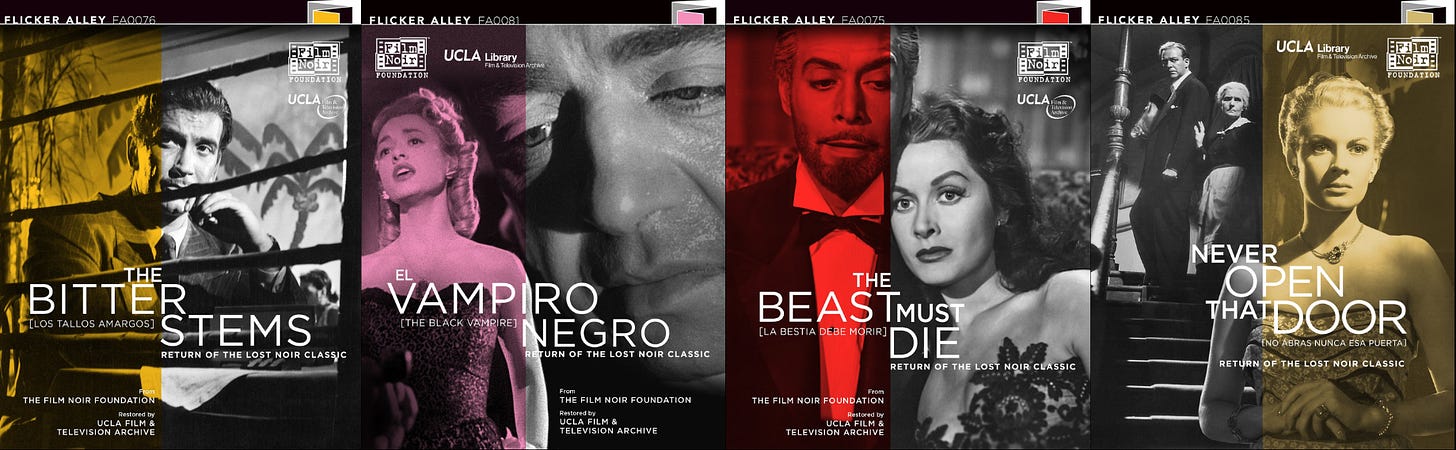

Thanks to the Film Noir Foundation, the UCLA Film & Television Archive, Fernando Martín Peña, and Flicker Alley, the riches of Argentine film noir have just begun to be available to noir fans on Blu-ray and DVD with titles such as The Bitter Stems (Los tallos amargos, 1956), The Black Vampire (El vampiro negro, 1953), The Beast Must Die (La bestia debe morir, 1952), and most recently, Never Open That Door (No abras nunca esa puerta, 1952), a film previously reviewed here at Journeys in Darkness and Light. While some of these titles may lead you to believe you’re in for a night of horror, rest assured: you’re in solid noir territory, a landscape filled with deception, betrayal, greed, and often revenge. What could be safer?

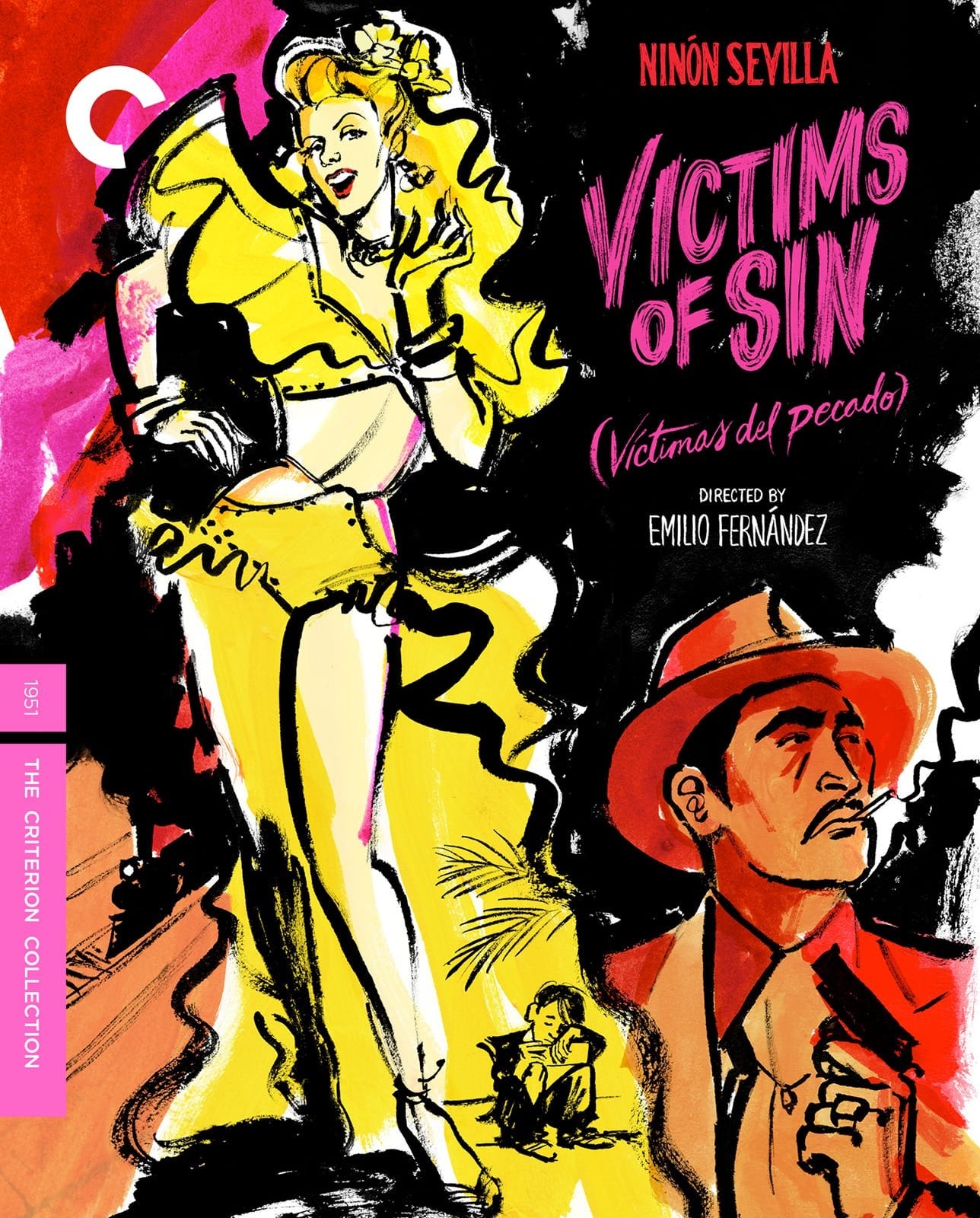

While the above films were all made in Argentina, Mexico produced an enormous wealth of noir in the 1940s and ‘50s, a motherlode of cinematic richness I’m just beginning to discover including a movie I’ve previously written about, Espaldas Mojadas (1955). Earlier this year when I opened the Criterion Collection’s monthly new releases email, I noticed the disc cover for Victims of Sin (Victimas del pecado, 1951), which appeared to contain elements of film noir. The film certainly delivers on the noir idea, yet also assaults the senses like a Category 5 hurricane ripping across the screen, combining scorching music and unbridled dancing in smoke-filled nightclubs lit with fluorescent neons. At this particular club, customers demand entertainment guaranteed to blow their minds and help them forget they are also patronizing a hangout for sleazy criminals and shady deals. What’s different about Victims of Sin is its unbridled musical sexual energy combined with depictions of ordinary workers, troubled souls forced to perform nightly, attempting to scrape up a living as waiters, dance hall girls, or worse, prostitutes. Yet this is just the beginning.

While Victims of Sin is a fine example of cabaretera movies critical of Mexican patriarchy featuring cabaret singers and dancers, it’s also a rumbera picture, focusing on Afro-Caribbean music imported to Mexican culture. The film’s star, Cuban-born Ninón Sevilla, plays Violeta, a dancer who packs the house every night performing seductive moves that seem to live inseparably from the percussive frenzy of the house band. But Violeta soon endangers herself and her career by stepping in where she’s not wanted. Rosa (Margarita Ceballos), a worker at the club and plaything of a local gangster/pimp named Rodolfo (Rodolfo Acosta), pleads with him to allow her to keep the newborn baby he fathered with her. When Rodolfo commands Rosa to put the child in the trash and return to work, Violeta refuses to stand by, promising to care for the infant. Then the noir elements really kick in. Revealing more would be criminal. Just don’t expect your typical American noir tropes to be delivered in quite the same way.

You get the feeling this is the type of picture Ida Lupino could’ve championed, yet the Production Code would never allow a movie like Victims of Sin to be released on American soil, which is one reason films from other cultures are so important. The picture’s brutality (including women who get slapped a lot, and sometimes by other women) and dark themes wouldn’t have played here, not even in the 1950s when Hollywood was beginning to explore the uglier side of life the Code seldom allowed.

In Noir City Magazine #25, Imogen Sara Smith writes, “Victims of Sin is like a fireworks show, one explosive climax after another.” There’s enough familiarity to think you can anticipate what’s coming next, then your expectations get waylaid. Each scene invites you to descend deeper into gender battles, class conflict, and the chaos of noir. As this Dante-like journey descends downward, viewers realize they’re watching something American noir fans rarely saw: a female-centric noir that pulls no punches.

Yet we feel for Violeta and her sacrifice, longing to see her emerge victorious. Many walking past the club might want to save a helpless child, but few will do anything to help. Violeta’s dedication to the baby comes at a huge personal cost, but we also keep asking ourselves, “Why would this woman take on such a burden? What’s in it for her?” Audiences are forced to contrast the darkness of the setting with the good they see in Violeta, something audiences sometimes witness in American film noir, but rarely like this. Catholic influences are often present in Spanish-language films, so that may account for some of Violeta’s behavior, but is she simply too good to be true? And is the rival club owner (Tito Junco) really interested in helping Violeta and the baby, or does he have something else in mind? Expect the unexpected.

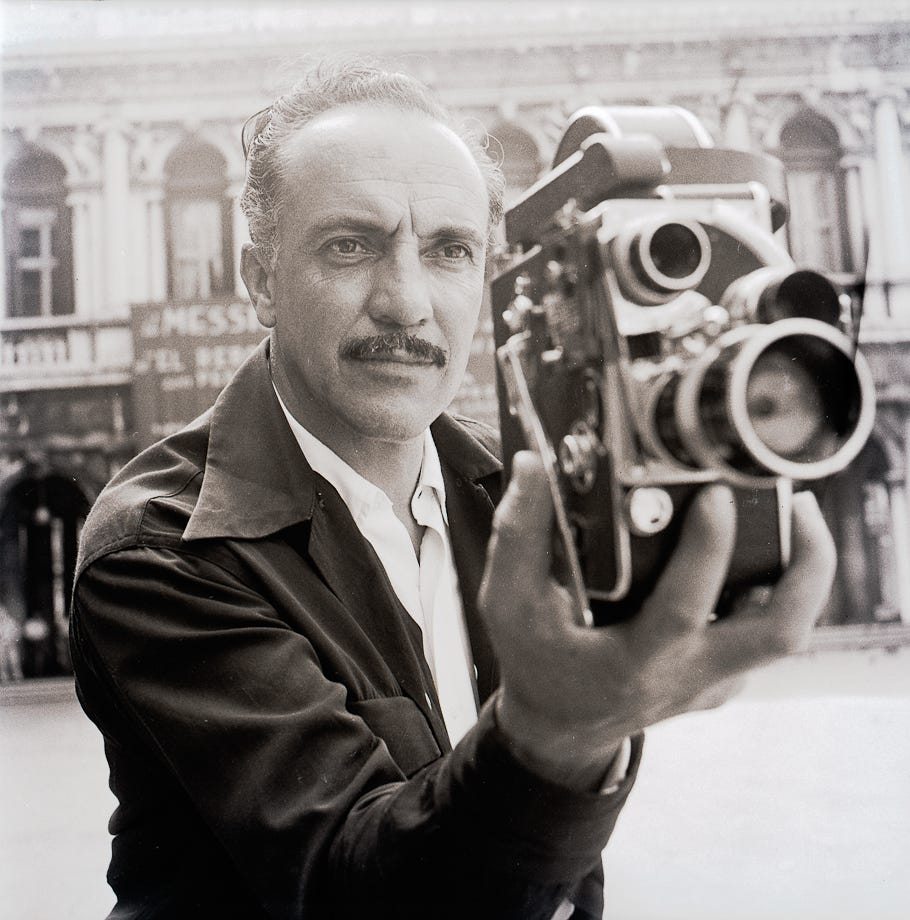

If they know him at all, most American movie fans recognize director Emilio Fernández (1904-1986) from his acting career, appearing in supporting roles such as General Mapache in The Wild Bunch (1969) and “El Jefe” in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974). But Fernández was a titan of Mexican cinema, writing and directing dozens of pictures and acting in more than 80. Fernández created a unique style in Mexican cinema that was a radical departure from Hollywood films from the same era, “Mexican stories, about Mexicans, for Mexicans,” FOOTNOTE p. 94) drawing upon Mexican art, culture, and literature to create a national style free from the stereotypes he saw of Mexicans portrayed in American films.

Fernández’s partnership with cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa (1907-1997) resulted in 24 films, several appearing on lists of the greatest Mexican films of all time. From 1945 to 1949, these collaborations dominated the Ariel Awards (Mexico’s equivalent of the Oscars) with an astounding 30 wins. With a brilliant eye for framing, composition, and the use of chiaroscuro, Figueroa set himself apart from other cinematographers. It probably didn’t hurt that his mentor was none other than Hollywood’s iconic cinematographer Gregg Toland. (The Criterion release contains extras that explore the lives and work of both men, particularly Figueroa.)

Victims of Sin isn’t even considered one of the best Fernández/Figueroa collaborations, but it still knocked me on my butt. If this is one of their lesser efforts, let’s hope Victims of Sin opens the door to an entire storehouse of Mexican cinema (and especially noir) on physical media. The film is currently playing on the Criterion Channel and the big screen at Noir City festivals. The Criterion Blu-ray is available now.