The Finest Robert Duvall Performance You’ve Never Seen: Tomorrow (1972)

As saddened as I am about Robert Duvall’s death, I love to see his work celebrated. Duvall had a long, outstanding career, and while I applaud everyone who watches (or rewatches) any of the actor’s performances, I’m betting few have seen him in a little-known film called Tomorrow (1972).

Based on William Faulkner’s short story of the same name, Tomorrow begins with a courtroom scene in rural Mississippi.1 A man named Bookwright is on trial for murdering a man named Buck Thorpe, a no-account blight on the local community who, according to all the locals, got what he deserved. Yet one ragged, time-worn man on the jury refuses to vote to acquit Bookwright. As the defense attorney narrates, “And so Jackson Fentry (Duvall), cotton farmer, hung my jury. Who was he? I thought he’d farmed one place all his life, but I discovered that 20 years ago he left for a job. His neighbors told me. You see, that was my first case, and I had to find out why I’d lost it.”

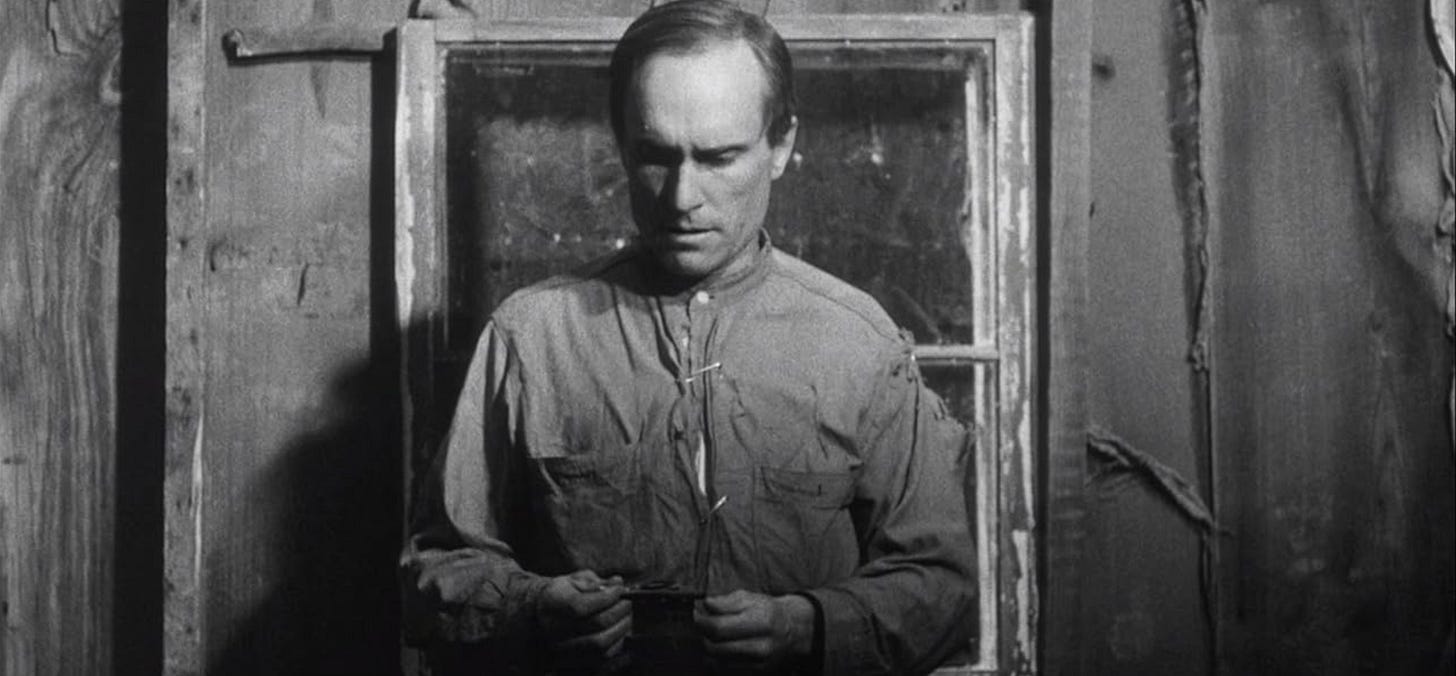

Flashback to a younger Fentry who has just been hired as caretaker of a backwoods sawmill for the winter until it can resume operations in the spring. The sawmill owner’s son (Richard McConnell) tells him the last man they hired couldn’t handle the isolation and turned to the bottle.

As winter begins, a pregnant woman named Sarah (Olga Bellin) appears on Fentry’s doorstep with no place to go. She’s extremely weak, and although Fentry has little to offer, he takes her in and cares for her. I hesitate to tell you more about the plot, so I’ll focus on the film itself, especially Duvall’s performance.

What most filmmakers get wrong about adapting Faulkner is the look and feel of his stories. In all the Faulkner novels and stories I’ve read, the South in general, and Mississippi in particular, is in a state of debilitating defeat brought on by the aftermath of the Civil War. Amidst this broken land Faulkner wraps the reader in a trounced atmosphere like a moth-eaten blanket with too many holes. What little comfort you can find there is fleeting. Too often Hollywood paints a picture of Faulkner’s landscapes as homey, somewhat rustic, but largely undamaged. Such ventures are doomed to failure; they fear to show what dejection, suffering, and defeat really look like and how Faulkner’s characters react to such situations.

However, Tomorrow gets it right, and Duvall nails it.

The film was shot in Mississippi, and places like those depicted are ones I’d seen many times as a kid, especially riding with my Uncle Billy in his truck delivering produce to country people you’d rarely (if ever) see in town. Those are the places of ramshackle homes, sheds or barns left uncompleted and rotting, rusted out cars and trucks in yards that hadn’t seen a lawnmower in months. Tomorrow is as authentic as it gets.

Olga Bellin spent most of her acting career in theatre and television. Her only other film credit is for voice work in the Ken Burns documentary The Shakers: Hands to Work, Hearts to God (1984). As Sheila O’Malley notes in her excellent essay on Tomorrow,

Sarah, as imagined by (Shelby) Foote and actress Bellin, is a weakened woman, running away with nowhere to go. She has a positive, chatty personality, all the more heartbreaking considering her brutal circumstances. Fentry’s promise that he will take care of her child no matter what happens to her is so heart-rending it practically ruptures the delicate fabric of the film. That is the intended effect. Bellin’s performance is more mannered than the rest of the cast, but it reflects Sarah’s persistent attempts to imagine herself into a better world: a house, a garden… She doesn’t ask for much, but even that has been denied her.

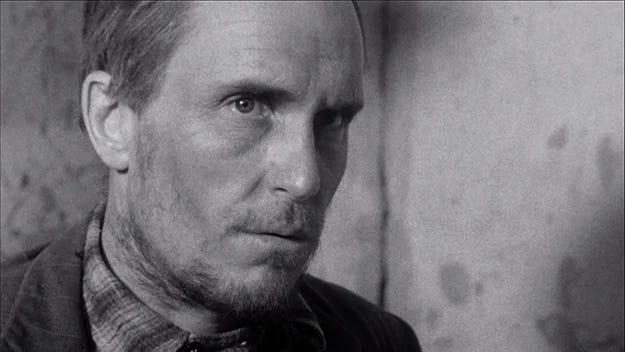

Yet Duvall’s performance is so authentic you’d think you’re watching a documentary. You might swear this isn’t an actor, but rather a man so quiet, so unused to conversing with anyone, his understated and halted speech has been with him his entire life. In taking care of a weakened and pregnant Sarah, Fentry realizes he’s the only hope she has and must find within himself a way to care for and comfort her with acts and words of kindness and encouragement. This is no easy task for such a quiet, solitary man. In an interview (also cited in the O’Malley article) about how he developed the character, Duvall stated,

“I once went with my brother to southern Missouri to spend a few days, and went into Arkansas and we met this guy. He didn’t open his mouth until he had something to say; he talked straightforward. He talked like a cow. Fentry was such a guy, a closed guy.” The effectiveness of the performance lies in the silences, its unexpected gentleness, the way he says bluntly: “Marry me, Sarah.” Duvall has said: “I still point to Fentry as my best part.”

The screenplay for Tomorrow was written by Shelby Foote, but this wasn’t the first time Duvall had worked from one of the writer’s scripts. Foote also wrote the screenplay for To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), which featured a brief but unforgettable Duvall performance as Boo Radley. Foote also penned the script for Tender Mercies (1983), a role that would earn Duvall his sole Best Actor Oscar.

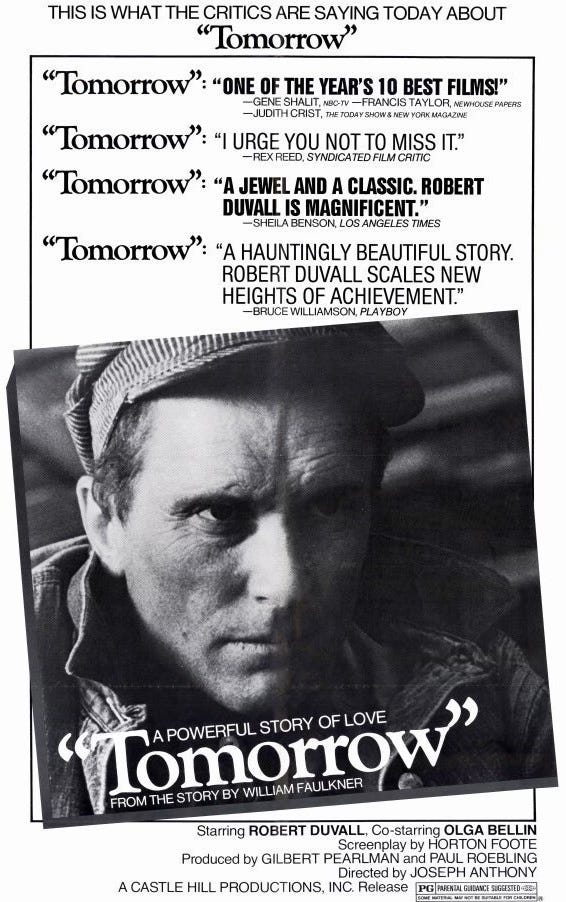

Although it was praised by several critics, Tomorrow had much working against it: It was an independent film with no major actors, shot in black-and-white, and had a limited release. Had it been distributed on a larger scale, many people who had seen Duvall’s Oscar-nominated performance as Tom Hagen in The Godfather (released just weeks before Tomorrow) would probably have gone to see it.

For those who haven’t watched it, I encourage you to seek out Tomorrow. It is currently available on Kanopy, which is available through many public libraries. Thanks for reading.

Although the time is not stated, the visuals seem to suggest the 1930s, which is somewhat in line with the 1940 publication of Faulkner’s short story “Tomorrow.”